The Root of Environmental Injustice at New York’s Founding

The history of structural racism in New York begins with colonization. Before the Dutch founded the colony of New Amsterdam in 1624, this land was part of Lenapehoking, a civilization of Lenape people that spanned across a vast region, including all of what are now called the five boroughs and present day New Jersey and the lower Hudson Valley, with Manahattan, known today as Manhattan, at its heart.25Lenapehoking. (n.d.). Brooklyn Public Library. Nonprofit Organization. The pre-colonization Lenape civilization was dense and populous, with as many as 15,000 people living in what became the five boroughs.26Native New Yorkers: The Legacy of the Algonquin People of New York. (2002). Pritchard, E. Council Oak Books. Book. By comparison, the non-Native population of New York did not reach that number until around the time of the American Revolution a century and a half later.27Population History of New York City. (1972). Rosenwaike, I. Syracuse University Press. Book. The Lenape built travel and trade routes through this land, including roads that later became Broadway in Manhattan and Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn. Due to its strategic location, Manahahtaan was a trading hub and seat of government in Lenapehoking.28Native New Yorkers: The Legacy of the Algonquin People of New York. (2002). Pritchard, E. Council Oak Books. Book.

When the Dutch arrived, they established exclusive possession of the land they settled on. They rapidly fortified their settlement, building a wall along what is now Wall Street to fence the Lenape out; and, piece by piece, grabbed more land, pushing the Lenape out or killing them. The Dutch (and later the British and French colonists) weakened the Lenape by destroying the environment, clearcutting forests, filling in marshes and streams, overhunting animals and fish, and overgrazing grasslands. They brought diseases that decimated the Native population, reducing it to a tenth of its original size.29Native New Yorkers: The Legacy of the Algonquin People of New York. (2002). Pritchard, E. Council Oak Books. Book. Ecological destruction and disease became tools of settler colonialism—tools that bolstered the settlers’ military strategy of genocide and domination.30, 3130: The Lenape: Archaeology, History, and Ethnography. (1986). Kraft, H. New Jersey Historical Society. Book.

31: Settler Colonialism, Ecology, and Environmental Injustice. (2018). Whyte, K. Environment and Society, 9(1). Academic Research.

As they wrested the land from the Lenape, the colonists used the forced labor of enslaved Africans and their descendants to transform land into a profitable asset within a globalizing, extractive, imperial economy. The Dutch West India Company, a for-profit enterprise, brought the first enslaved people to “New Amsterdam” in 1626. The Dutch forced these and future enslaved people to build much of the colony’s earliest infrastructure, including Fort Amsterdam and Broadway.32In the Shadows of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. (2004). Harris, L. Chicago University Press. Book.

When the British gained control of the colony, they increased imports of enslaved people, implementing ever-harsher laws that entrenched slavery in the colony’s legal system and legally subordinated Black people. As a result, New York became the capital of slavery in the North: in 1703, 42 percent of white households owned enslaved people, more than any North American city except Charleston, South Carolina. It was through the forced labor of these enslaved people that New York’s Dutch, British, and American colonizers transformed Manhattan from a small farm settlement into a wealthy global port city.33, 34 33: Ibid. 34: The Hidden History of Slavery in New York. (2005). Oltman, A. The Nation. News Article.

The Burdens and Benefits of Growth: New York in the 19th Century

Castello Plan New Amsterdam in 1660.

The 19th century was a period of rapid growth and change during which New York City transformed from an important but relatively small port town to a bustling metropolis. Migration (both foreign and domestic) made New York’s population boom from 60,515 in 1800 to 3,437,202 by the end of the century.351790—2000 NYC Historical and Foreign Born Population. (2000). NYC DCP. NYC Government. At the same time, rapid, largely unregulated industrialization degraded the environments where growing numbers of New Yorkers lived and worked, creating a public health crisis that disproportionately impacted the poor, immigrants, and people of color. In response, New York made massive investments in public infrastructure, including the sewer and water systems and many of our parks. These investments brought huge public health benefits, but these benefits were not always equally distributed, and in some cases, benefits for the privileged came at the expense of marginalized groups.

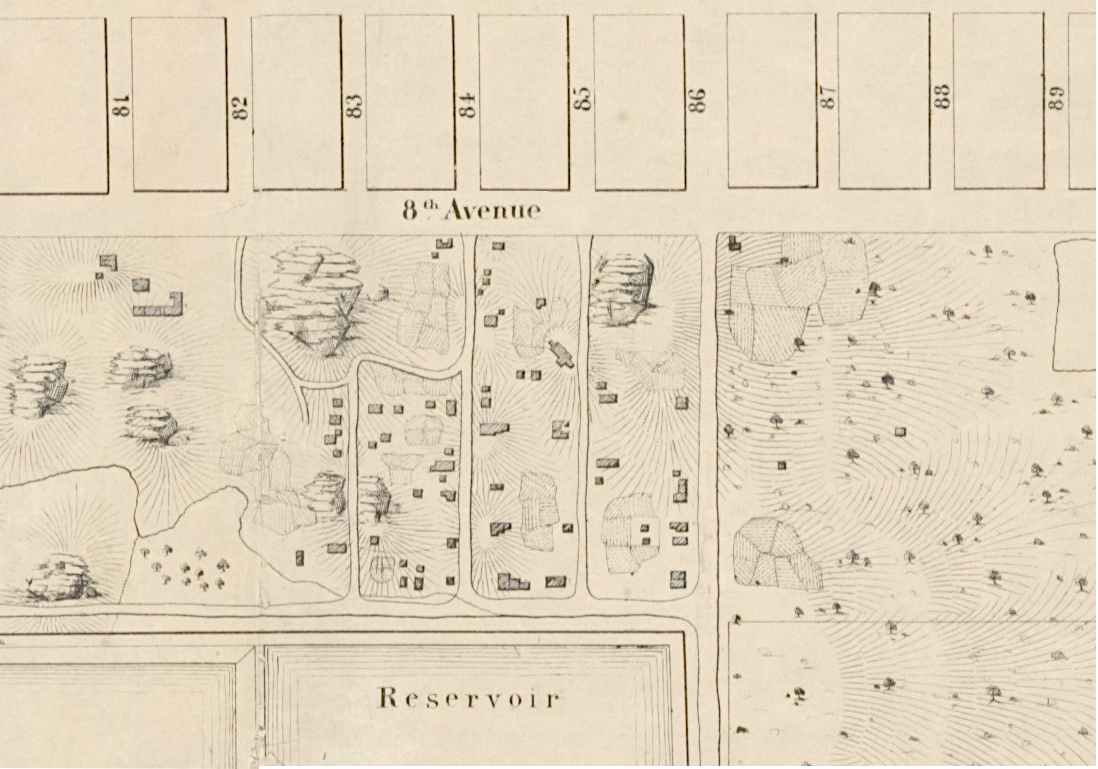

One such case was that of Seneca Village. Located between present-day 82nd and 89th Streets and 7th and 8th Avenues, Seneca Village was a prosperous and predominantly Black community.36Unearthing Traces of African-American Village Displaced by Central Park. (2011). Foderaro, L. The New York Times. News Article. Its residents were largely working- class, but many were able to attain property ownership and were building wealth. They had founded two churches, A.M.E. Zion and the African Union Church, as well as a school.37In the Shadows of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. (2004). Harris, L. Chicago University Press. Book. When the City made plans to build Central Park in the 1850s, Seneca Village was acquired through eminent domain. All the homes, churches, school, and businesses were leveled by the City.38Before Central Park: The Story of Seneca Village. (2018). Central Park Conservancy. Nonprofit Organization. This is an example of environmental injustice by conferring a benefit to the public overall at the expense of working-class Black property owners, disenfranchising a thriving community.

In the latter half of the 19th century, environmental and public health crises brought on by rapid industrialization and urbanization accelerated. Each decade, hundreds of thousands of additional New Yorkers were born in or came to the city seeking better lives. Poor residents lived in crowded tenements, lacking access to basic sanitary services, and they worked in dangerous, unregulated industrial workplaces. Living conditions resulted in striking health and mortality disparities between the poor and rich. Infectious diseases such as cholera, typhus, typhoid fever, and dysentery killed thousands of New Yorkers every year, most of them in slums. Because overcrowded tenements lacked access to clean water and adequate waste disposal, residents were vulnerable to waterborne diseases that periodically swept through the city in devastating epidemics.

The tide of infectious disease began to shift as improvements in public infrastructure brought clean water and sanitation to more New Yorkers. In response to rampant disease, the City and private groups began investigating the connection between the environment and health in the mid-19th century; the Departments of Health and Sanitation were founded in 1870 and 1881, respectively. Building on this emerging understanding of environmental health, the City implemented reforms that dramatically improved public health outcomes. In 1842, the City completed work on the Croton Aqueduct, for the first time bringing clean municipal water to its residents. A few years later in 1849, it began building the sewer system.

Benefits for the poorest New Yorkers materialized slowly; at first, the Aqueduct and sewer served wealthy New Yorkers who had access to pipes and water hookups.39Water for Gotham: A History. (2001). Koeppel, G. Princeton University Press. Book. Outbreaks of cholera and other waterborne diseases persisted in the city’s slums, with deeply unequal and deadly results. But the City continued to increase municipal water and sewer capacity through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, all but eradicating those diseases by the early 20th century.40How New York City Found Clean Water. (2019). Schifman, J. Smithsonian Magazine. News Article., 41Mapping Cholera: A Tale of Two Cities. (2014). Shah, S. Pulitzer Center. Nonprofit Organization. Ultimately, the greatest improvements from these public health interventions accrued to low-income people, particularly Irish and Black residents, because these groups had been the hardest hit by waterborne diseases.42Protecting Public Health in New York City: 200 Years of Leadership. (2005). NYC DOHMH. NYC Government.

On the waterfront, working-class communities often lived in the environments where they worked: industrial areas with docks, factories, refineries and sewer discharges. Industrial pollution in Newtown Creek, Brooklyn, for example, dates to the 17th century, with the country’s first kerosene and oil refineries.43History of Newtown Creek. (n.d.). Newtown Creek Alliance. Nonprofit Organization., 44Newtown Creek. (2020). NYS Department of Health. NYS Government. Investment in port facilities grew industrial activity along Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal, home to coal, oil, and chemical processing facilities; a cement plant; and a tannery. The New York Harbor and working waterfronts along the Hudson and East Rivers also had working-class residential neighborhoods within heavy industrial areas.

The history of industrialization that began along New York’s waterways in the 19th century extended into the 20th and 21st centuries. Today, Newtown Creek and the Gowanus Canal are both designated Superfund sites because of pollution that dates to the 19th century and continued into the 20th century.45Environmental Justice Tour. (2022). Gould, K., Lewis, T., and Tumpson Molina, E. Excerpt from in A People’s Guide to New York City. University of California Press. Book., 46Superfund Site: Newtown Creek, Brooklyn, Queens, NY. (n.d.). US EPA. US Government., 47Superfund Site: Gowanus Canal, Brooklyn, NY. (n.d.). US EPA. US Government. In Newtown Creek, for example, industrial parties leaked between 17 and 30 million gallons of oil, as well as tar and other chemicals into the creek over the course of several decades, in flagrant disregard of health and safety. 48Environmental Justice Tour. (2022). Kenneth A. Gould, Tammy L. Lewis, and Emily Tumpson Molina. Excerpt from in A People’s Guide to New York City. University of California Press. Book. The history of industrialization in New York City continues to be felt by residents of EJ communities today, as described in Exposure to Hazardous Materials.

Land Use and Housing Segregation in the 20th Century

Seneca Village near 81st and 89th Streets and 8th Avenue

In the 19th century, development in New York City was largely unregulated, contributing to overcrowding, public health concerns, and lower property values.49Report of the Heights of Buildings Commission to the Committee on the Height, Size and Arrangement of Buildings of the Board of Estimate and Apportionment of the city of New York. (1913). Heights of Buildings Commission. NYC Government. In 1916, the City adopted its first zoning ordinance, and in doing so gained a powerful new tool to shape the urban environment. Zoning is the process by which local governments carry out planning policy through organizing the types and densities of land uses (residential, commercial, industrial, or mixed-use) allowed in each area of the city. In the 1916 code, the city was divided into residential, commercial and unrestricted zones. Unrestricted zones had no regulations or restrictions, meaning that industrial uses could be sited alongside residential uses and vice versa.50Zoning Law, Health, and Environmental Justice: What’s the Connection? (2002). Maantay, J. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, Then, in 1961, the City overhauled its zoning code to separate land uses by type, rezoning unrestricted areas as either Residential (“R”) or Manufacturing (“M”). The rezoning of the unrestricted areas were, in part, shaped by existing industrial development patterns that pre-date the 1916 zoning ordinance. Growing industrial activity during that time was often located near transportation, waterways, and dense concentrations of labor.51Citywide Industry Study. (1993). NYC DCP. City Government. Additionally, city planners factored existing land use trends into their rezoning decisions; however, inconsistencies in final designations raised concerns of potential racial bias.52Zoning Law, Health, and Environmental Justice: What’s the Connection? (2002). Maantay, J. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics,

Residential mortgage lending was another tool that influenced development patterns during this time. The Home Owners’ Loan Act of 1933 established two federal agencies to support the residential housing market during a period of rising mortgage defaults: the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). The FHA was created to provide an “economically sound” publicly sponsored mortgage lending system to stimulate growth in the economy through residential home construction.53New Evidence on Redlining by Federal Housing Programs in the 1930s. (2021). Fishback, P., Rose, J., Snowden, K., and Storrs, T. National Bureau of Economic Research. Nonprofit Organization. However, the FHA largely excluded Black homeowners living in low-income urban neighborhoods from its insured loans, which perpetuated residential segregation.54New Evidence on Redlining by Federal Housing Programs in the 1930s. (2021). Fishback, P., Rose, J., Snowden, K., and Storrs, T. National Bureau of Economic Research. Nonprofit Organization.

The HOLC, a temporary agency intended to support homeownership for Americans by refinancing home mortgages during an economic downturn, created its own “residential security maps” that charted the supposed riskiness of issuing mortgages in neighborhoods across the country. In a process commonly known as redlining, the maps ranked neighborhoods as “A (Best)” in green; “B (Still Desirable)” in blue; “C (Definitely Declining)” in yellow; or “D (Hazardous)” in red. HOLC assessed each neighborhood based on its percentage foreign- born population, percentage Jewish population, percentage Black population, and whether any of these groups were “infiltrating.” By explicitly using race and ethnicity as central determinants of a neighborhood’s property value, the maps reinforced existing patterns of residential segregation.55New Perspectives on New Deal Housing Policy: Explicating and Mapping HOLC Loans to African Americans. (2019). Michney, T. and Winling, L. Journal of Urban History, 46(1). Academic Research. In Brooklyn, not one of the 18 neighborhoods that had any Black population received a better than a “C” grade, and any neighborhood that had a greater than 5 percent Black population received a “D” grade.56A Covenant with Color. (2001). Wilder, C. Columbia University Press. Book. HOLC’s maps contributed to a racist perception among some white New Yorkers that the mere presence of Black residents was enough to depreciate property values—these maps are now viewed as deliberate, systematic racism perpetrated by the government.57The Color of Law. (2017). Rothstein, R. Liveright. Book.

By labeling Black, Jewish and immigrant communities as unstable areas for mortgage lending, redlining legitimized the sentiment that low-income communities and communities of color are less valuable than white communities. Redlining became a self-fulfilling prophecy: the restriction of financial resources into redlined neighborhoods hindered the ability of residents to purchase homes, invest in properties, and start businesses, subsequently suppressing land values and limiting economic opportunities.58A brief history of redlining. (2021). NYC DOHMH. NYC Government. It created a cycle of disinvestment in communities of color and low-income communities, where polluting infrastructure could most easily be sited. These economic conditions, coupled with a lack of civic infrastructure tied to homeownership, made these communities prime destinations for siting the city’s most undesirable facilities.

During this same period, white homeowners, particularly those in suburban areas, benefited from generous public subsidies that allowed them to build intergenerational wealth. These generous public subsidies were designed to relocate white homeowners outside of the city, and it worked; many Black homeowners lost wealth as a result of these policies, while many White homeowners were given a government subsidized opportunity to generate wealth.59New Perspectives on New Deal Housing Policy: Explicating and Mapping HOLC Loans to African Americans. (2019). Michney, T. and Winling, L. Journal of Urban History, 46(1). Academic Research.

Beginning with the New Deal, subsidized home loans to white New Yorkers helped them accumulate wealth, and this wealth ultimately enabled them and their children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren to more easily access safe and healthy housing.60See, for example: The Color of Law. (2017). Rothstein, R. Liveright. Book. At the same time, government-funded public housing projects were often segregated and unequal. In the late 1930s, for example, NYCHA opened Harlem River Houses for Black residents and Williamsburg Houses for white residents.61The Color of Law. (2017). Rothstein, R. Liveright. Book. In the words of Harlem-based newspaper The People’s Voice, these segregated projects were “crystallizing patterns of segregation and condemning thousands of Negroes to a secondary citizenship status for generations to come.”62To Stand and To Fight: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Postwar New York City. (2003). Biondi, M. Harvard University Press. Book. In other cases, the government funded housing developments only for white New Yorkers without creating analogous projects for Black New Yorkers, further contributing to racial inequities in housing access.

Starrett City, the largest subsidized housing development in the country, initially filled vacancies through racial quotas: 62 percent white tenants, 23 percent Black tenants, 9 percent Hispanic tenants, and 6 percent Asian tenants or other tenants of color.63Court Upholds Ruling Against Racial Quotas for Starrett City. (1988). Lubasch, A. The New York Times. News Article., 64A Dilemma Grows in Brooklyn. (1988). Hellman, P. New York Magazine. Magazine Article As a result, Black tenants were waiting nearly eight times as long as white applicants to get an apartment in the development. In 1984, the U.S. Justice Department sued Starrett City, on the basis that the racial quota system violated anti-discrimination laws.65U.S. Challenges Accord in Starrett City Bias Suit. (1984). Fried, J. The New York Times. News Article. The Court ruled that the racial quotas were in fact unlawful.66Court Upholds Ruling Against Racial Quotas for Starrett City. (1988). Lubasch, A. The New York Times. News Article.

Taken together, these and other policies perpetuated racial segregation and contributed to disparities in access to resources and health outcomes between white residents and residents of color. While the use of redlining maps became illegal following the adoption of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, the effects of this policy continue to be felt today and are deeply intertwined with environmental injustice.

Disinvestment and Health Inequitiesin New York’s EJ Communities

A closer examination of redlined areas indicates that “low risk” neighborhoods were generally located away from environmental burdens, while low-income communities and communities of color were generally clustered near environmental burdens. These included hazards that were connected to government-owned and operated infrastructure, such as expressways and airports. More often, hazards emanated from privately owned and operated facilities. Many large-scale industrial facilities known to contribute to air pollution, including power plants and solid waste facilities, were legally constructed in and around EJ communities. So, too, were smaller-scale pollution sources such as auto body shops and dry cleaners built in manufacturing districts abutting EJ communities. At the same time, communities of color and low-income communities experienced disinvestment, and were denied equal access to housing, green space, and solid waste pickup, exacerbating environmental hazards such as unhealthy housing, extreme heat, dirty streets, and pests such as rats and insects.67, 68, 6967: “Taxation without Sanitation Is Tyranny”: Civil Rights Struggles over Garbage Collection in Brooklyn, New York, during the Fall of 1962. (2007). Purnell, B. Afro-Americans in New York Life and History, 31(2). Academic Research.

68: Where We Live NYC. (2020). NYC HPD. NYC Government.

69: How Decades of Racist Housing Policy Left Neighborhoods Sweltering. (2020). Plumer, B. and Popovich, N. The New York Times. News Article.

Environmental injustice affects all aspects of the built and natural environments in cities: water, soil, and air pollution; greenspace access and environmental service provision; and less traditionally “environmental” issues such as housing quality, traffic safety, and policing. The following discussion, divided into three sections on mobile and stationary source air pollution, unhealthy housing and indoor environments, and environmental service provision, offers a glimpse of the relationship between environmental injustice and health inequities. While not exhaustive, it makes clear that New York’s EJ communities face myriad compounding injustices that interact in complex and often hidden ways to contribute to inequitable health outcomes.

Mobile and Stationary Air Pollution

In the twentieth century, city planners began supporting automobile ownership and use for affluent white suburbanites. Inequitable commuter infrastructure and car ownership created additional environmental injustices in the form of air pollution, highways that divided neighborhoods and destroyed homes, and traffic violence. When the Cross-Bronx Expressway was built in 1955, it tore through the heart of the Bronx and displaced approximately 40,000 residents, most of them Jewish, Irish, Italian, and Black.70Mayor Adams Kicks off Landmark Study to Reimagine Cross-Bronx Expressway. (2022). NYC Office of the Mayor. NYC Government., 71Sustainable Communities in the Bronx: Leveraging Regional Rail for Access, Growth & Opportunity. (2014). NYC DCP. NYC Government. This created a deep divide within a tight-knit community— destroying homes, businesses, and a once-thriving open market on Bathgate Avenue.72Robert Moses: The Expressway World. (1988). Berman, M. Excerpt from All That is Solid Melts into Air. Penguin Books. Book.

The Gowanus Expressway, built in 1941, similarly displaced thousands of people and destroyed a bustling commercial corridor along Third Avenue in Sunset Park, Brooklyn.73Construction of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. (2023). Segregation by Design. Video., 74Developers Compete to Shape the Future of Brooklyn’s Sunset Park. (2016). Kensinger, N. Curbed NY. News Article. The Gowanus Expressway is a prime example of the cascading impacts created by major infrastructure projects. By facilitating truck traffic, the expressways accelerated the industrialization of areas already stricken by industrial pollution.75Burying Robert Moses’s Legacy in New York City. (2004). Freilla, O. Excerpt from Highway Robbery: Transportation Racism & New Routes to Equity. Book.

HOLC Map of the Bronx

In a process commonly known as redlining, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC)—a New Deal federal agency intended to support homeownership for Americans by refinancing home mortgages during an economic downturn—created “residential security maps” that charted the supposed riskiness of issuing mortgages in neighborhoods across the country.

Cross-Bronx Expressway Construction, 1952. SOURCE: CUNY Academic Commons

Cars, which Largely Benefited the Affluent White Suburbanites Who Could Afford Them for Their Commutes into the City, Created Myriad Environmental Injustices for the Communities They Sped Through.

As the Gowanus Expressway example demonstrates, industrial land uses and vehicle infrastructure have a mutually reinforcing relationship that compounds hazards in environmental justice communities. Vehicle infrastructure enables and attracts industrial uses, and industrial uses generate vehicle traffic. In particular, land uses such as warehouses and logistics centers, last-mile delivery facilities, bus depots, and waste transfer stations, which have all disproportionately been sited in New York’s low-income communities and communities of color, attract heavy bus and truck traffic to those neighborhoods. These heavy-duty vehicles are often diesel-powered and produce emissions that are even more damaging to human health than those produced by gasoline-powered passenger vehicles. Traffic is a major source of PM 2.5, or fine particulate matter, which can cause health problems to the respiratory and circulatory systems and can decrease life expectancy.76The Public Health Impacts of PM2.5 from Traffic Air Pollution. (2021). NYC DOHMH. NYC Government.

The 20th century also saw the proliferation of stationary sources of air pollution, including power plants, waste incinerators, and other publicly- and privately-owned industrial facilities. The New York Independent System Operator (NYISO), the nonprofit corporation that oversees New York State’s bulk energy grid, requires facilities to sustain generating capacity within the five boroughs to maintain resilience during disruptions to imported power. Beginning in the 1960s, the State approved the construction of “peaker” power plants to ensure power reliability during times of peak demand. Although they operate infrequently, peaker plants are often switched on during high heat days when air quality is already stressed, in order to meet increased air conditioning power demand. Emissions from baseload generation plants are known to exacerbate multiple respiratory and pulmonary diseases, and when operating, peaker plants typically emit more particulate matter than baseload plants.77The Peaker Problem. (2022). Clean Energy Group and Strategen. Research Organization. Several peaker plants are still in operation today, including in EJ neighborhoods such as the South Bronx, South Williamsburg, Astoria, and Sunset Park.78Dirty Energy, Big Money. (2020). PEAK Coalition. Community Organization.

As recently as 2001, the New York Power Authority (NYPA), a State-owned utility, sited a dozen new power plants at seven sites across New York City as part of its PowerNow! program. These plants were presented to the public as a temporary solution to prevent summer power shortages but they remain in operation today. All of them are sited in or adjacent to EJ neighborhoods.79New York Power Authority Power Generation in the New York City Area. (2001). NYS Comptroller. NYS Government. Peaker plants and EJ neighborhoods are often co-located in industrial areas due to zoning, placing an unfair share of the environmental burden of energy production on these residents. In 2023, New York State Legislature passed the Build Public Renewables Act, which requires NYPA to transition to 100 percent clean energy by 2030. This includes a provision to shut down all NYPA-owned peaker power plants by 2030, a significant win for EJ communities impacted by these facilities.

Unhealthy Housing and Indoor Environments

Environmental injustice extends to New Yorkers’ most intimate environments: their homes. In New York City, housing quality has been vastly unequal, with low-income people and people of color disproportionately exposed to hazards such as lead in paint, asbestos, mold, and pests. These disparities stem in part from racist housing policies such as redlining which prevented people of color, especially Black people, from attaining homeownership, building wealth, and investing in housing quality improvements.80, 8180: Health, housing, and history. (2021). NYC DOHMH. NYC Government.

81: The Color of Law. (2017). Rothstein, R. Liveright. Book.

Today, people of color still make up a disproportionate share of New Yorkers living in public housing and in housing assistance programs such as Section 8—properties which have higher rates of home-related health hazards such as pests, mold, and maintenance deficiencies.82Where We Live NYC. (2020). NYC HPD. NYC Government. The result is that Black and Hispanic or Latino households are more likely to live in housing with maintenance deficiencies and more likely to have higher asthma- related hospital utilization rates, compared to white households.83Where We Live NYC. (2020). NYC HPD. NYC Government.

Unequal Benefits and Burdens of Environmental Service Provision

Already overburdened by pollution, EJ communities have also been denied equitable access to essential environmental services. These include recreational spaces such as parks, playgrounds, and pools; natural resources such as street trees; and services such as sanitation and street cleaning. During the 1930s, the City built 255 playgrounds using federal funding, that were disproportionately sited in wealthy and white neighborhoods.84An Administration with Rural Roots Now Must Address the Cities. (1977). Reinhold, R. The New York Times. News Article. Disproportionately high police presence, compounded with a lack of access to public space, left Black children without many safe spaces to play. As one Stuyvesant Heights mother said, “the police just keep the kids moving and there is no place to send them.”85The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. (1974). Caro, R. Vintage Books. Book.

In the mid-20th century in Black and Hispanic/ Latino neighborhoods such as Bedford-Stuyvesant and East Harlem, the City neglected to regularly collect trash, provide trash receptacles on the street, or perform street sweeping, which led to notoriously dirty conditions on streets where children played and neighbors gathered.86“Taxation without Sanitation Is Tyranny”: Civil Rights Struggles over Garbage Collection in Brooklyn, New York, during the Fall of 1962 . (2007). Purnell, B. Afro-Americans in New York Life and History, 31(2). Academic Research., 87When the Young Lords Put Garbage on Display to Demand Change. (2021). Fernandez, J. History. News Article. Trash can attract pests and pollute the soil, air, and water, negatively impacting human health.88Why trash is a public health issue. (2023). NYC DOHMH. NYC Government. Residents in these neighborhoods fought back against this neglect in some of the earliest EJ mobilizations in the country. In 1962, the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equity (CORE) collected trash in Bedford- Stuyvesant and dumped it on the steps of Brooklyn’s Borough Hall in protest of discriminatory treatment by the Sanitation Department.89“Taxation without Sanitation Is Tyranny”: Civil Rights Struggles over Garbage Collection in Brooklyn, New York, during the Fall of 1962 . (2007). Purnell, B. Afro-Americans in New York Life and History, 31(2). Academic Research. In 1969, the Young Lords organized a similar action in East Harlem (dubbed the “Garbage Offensive”) heaping garbage at key intersections to force the Department of Sanitation to face the consequences of its neglect.90When the Young Lords Put Garbage on Display to Demand Change. (2021). Fernandez, J. History. News Article. In more recent times, the Department of Sanitation has taken major strides to integrate equity concerns into its programs. See A Closer Look at Waste Transfer Stations for more information.

EJ communities were not only excluded from the benefits of sanitation but disproportionately harmed by the siting of sanitation facilities. Beginning in the 1980s, the City began efforts to reduce dependence on the Fresh Kills landfill in Staten Island. This led to a proliferation of privately-operated waste transfer stations in EJ communities across New York City.91New York City Nonprofit Advocacy Case Studies: Case Study 1, Solid Waste Management and Environmental Justice. (2011). Baruch College School of Public Affairs Center for Nonprofit Strategy and Management. Academic Institution. In 1996, Mayor Rudy Giuliani and Governor George E. Pataki jointly announced plans to permanently close the landfill by 2001, and they also agreed to support a ban on the use of waste incinerators. While the ban was seen as a victory in many EJ communities, Fresh Kills’ closure further increased reliance on waste transfer stations, which are private lots where commercial waste is sorted or transferred before being transported outside of the city’s boundaries.92New York City Nonprofit Advocacy Case Studies: Case Study 1, Solid Waste Management and Environmental Justice. (2011). Baruch College School of Public Affairs Center for Nonprofit Strategy and Management. Academic Institution. Since the closing of Fresh Kills, over 75 percent of the city’s waste is now sorted or transferred in EJ communities.93Waste Equity. (n.d.). NYC Environmental Justice Alliance. Community Organization.

The Fight for Environmental Justice from the Late 20th Century to the Present

Beginning in the latter half of the 20th century, New Yorkers joined a worldwide movement for environmental justice. While people had been organizing for healthy environments for centuries, EJ organizers built a powerful movement based on the conviction that all people have the right to a healthy environment. Worldwide and in the U.S., the EJ movement is based on a framework of anti-racism, Indigenous sovereignty, and self- determination.94The Principles of Environmental Justice (EJ). (1991). Delegates to the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. Community Organization. In the U.S. it also is rooted in the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Civil rights activists secured the foundational rights that underpin environmental justice, chiefly equal protection under the law. They also built a powerful coalition of organizations that later coordinated some of the earliest EJ campaigns. The EJ movement is strongly rooted in racial justice and premised on an intersectional rights- based framework.

Since the 1970s, New York City has been working to better integrate environmental considerations into land use and facility siting decisions. The 1977 adoption of the City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) process was the first major act to systematize environmental review in City decision-making. In 2013, EJ advocates under the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance (NYC- EJA) coalition organized for waterfront justice in Significant Maritime Industrial Areas (SMIAs), which are the special designated areas of the city for clustering heavy industrial and maritime activity. Their work helped ensure that environmental and climate justice considerations were incorporated into City waterfront planning processes that impact land use decisions in New York’s waterfront EJ communities.95, 9695: New York City Environmental Justice Alliance Waterfront Justice Project. (2014). Bautista, E., Hanhardt, E., Camilo Osorio, J. and Dwyer, N. The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 20(6). Academic Research.

96: Waterfront Justice Project. (n.d.). NYC Environmental Justice Alliance. Community Organization.

The Environmental Justice Movement is Based on a Framework of Anti- Racism, Indigenous Sovereignty, and Self- Determination.

In conjunction with these land use- and siting- related efforts, New York City has seen major progress in efforts to remediate contamination from historical land uses and lead-based paint. In the late 1990s, a coalition of EJ, business, legal, and environmental groups, along with the City, were powerful advocates for the adoption of New York State’s Brownfield Cleanup Law.97Brownfield Cleanup Program. (n.d.). NYS Department of Environmental Conservation. NYS Government. Since the Office of Environmental Remediation (OER)’s creation in 2009, the City has established its own Voluntary Cleanup Program to oversee cleanups using NYS soil standard and administered a Brownfield Incentive Grant Program that empowers community-based organizations to plan for, investigate, remediate, and redevelop potentially contaminated sites and neighborhoods. The City’s efforts to remedy legacy contaminants addresses hazards in New Yorkers’ homes. Since 1997, the City has administered a Lead Hazard Reduction grant program that provides property owners with funding to remediate lead paint and other hazards in eligible buildings occupied by low-income residents.98Lead Hazard Reduction and Healthy Homes—Primary Prevention Program (PPP). (n.d.). NYU Furman Center CoreData NYC. Academic Institution., 99Lead Hazard Reduction and Healthy Homes Program. (n.d.). NYC HPD. NYC Government. These and other programs have made progress toward remediating legacy hazards.

DSNY Staten Island transfer station

A Closer Look at Waste Transfer Stations

In the past two decades, the City has taken steps to improve EJ outcomes related to solid waste management. Rising tipping fees (which are landfill disposal fees), and the phased closure of the Fresh Kills landfill in the 1990s contributed to the proliferation of private waste transfer stations in EJ communities.100New York City Nonprofit Advocacy Case Studies: Case Study 1, Solid Waste Management and Environmental Justice. (2011). Baruch College School of Public Affairs Center for Nonprofit Strategy and Management. Academic Institutions.In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the City imposed increasingly stringent regulatory controls on these transfer stations, which led to a reduction in the overall number of sites from 153 to 58 by 2013.101 A new front in the war over ‘waste equity.’ (2014). Giambusso, D. Politico. News Article. In 2006, the City adopted a Solid Waste Management Plan (SWMP), crafted in response to and with collaboration from EJ advocates. The SWMP began to address the unequal burdens of solid waste by shifting residential waste management from a truck-based waste hauling system to a barge- and rail-based system and by allocating the burden of waste transfer more equally among boroughs.

Since the adoption of the 2006 SWMP, New Yorkers have benefited from other laws and initiatives that aim to reduce the unequal burden of solid waste management. These include regulations on siting waste transfer stations and requirements for cleaner waste hauling trucks. In 2018, the City enacted the Waste Equity Law, directing the Department of Sanitation to reduce capacity at commercial transfer stations in four historically overburdened Community Districts. The following year, the City adopted the Commercial Waste Zones Law, which will consolidate the city’s commercial waste hauling under regulated zones, making the system more efficient and reducing associated diesel truck traffic by more than 50 percent. Together, these initiatives represent a historic and necessary shift toward equity and environmental justice in New York City’s waste management systems and serve as inspiration for future efforts to revaluate the siting of polluting infrastructure.

The City has also made strides to mitigate or phase out operational sources of air and water pollution. In 1996 New York State’s Clean Water/Clean Air Bond Act funded environmental remediation projects such as phasing out and replacing coal furnaces at 18 New York City schools.102Coal Furnaces at 18 Schools to Be Replaced. (1997). Hernandez, More recently, in 2010, the Department of Environmental Protection adopted its Green Infrastructure Plan, launching a multi-decade effort to reduce water pollution from combined sewer overflows by mitigating stormwater flow to the sewer system.103NYC Green Infrastructure Plan. (2010). NYC DEP. NYC Government. In 2023, the Department of Environmental Protection committed to spend $3.5B to expand the 2010 green infrastructure program to address both combined sewer overflows and stormwater runoff, with a focus on EJ communities.1042022 NYC Green Infrastructure Annual Report. (2022). NYC DCP. NYC Government. In 2012, the City’s Clean Heat Program began phasing out heavy residual heating oils in buildings that contribute to indoor and outdoor air pollution, leading to significant improvements in air quality.105Evaluating the Impact of the Clean Heat Program on Air Pollution Levels in New York City. (2021). Zhang, L., He, M., Gibson, E., et al. Environmental Health Perspectives, 129(12). Academic Research. And in 2013, a coalition of environmental groups, EJ advocates, academics, and local elected officials won a decade-long campaign to shut down NYPA’s Poletti peaker plant, which had been polluting the air in Astoria, Queens since the 1970s.106Shutting Down Poletti: Human Rights Lessons from Environmental Victories. (2018). Rebecca M. Bratspies. Wisconsin International Law Journal, 36(2). Academic Research.

Through these and many other programs, the City has taken steps to repair the destructive legacies of past decisions. In this work, the City has been encouraged and aided by EJ advocates’ tireless advocacy and collaboration. The City is committed to learning from its history and continuing to repair past harms, and to examining the ways that ongoing programs and processes may unintentionally contribute to unjust outcomes. The following sections of this report will assess existing programs and processes to evaluate their impact on environmental justice in New York City.

Environmental Justice Today and Tomorrow

Community organizations and government agencies continue to work to secure healthy, safe environments for New Yorkers and build thriving communities across the city. However, low-income communities and communities of color continue to be disproportionately exposed to environmental burdens, resulting in unequal health outcomes. These disparities are connected to legacies of racist policies that inflicted environmental harm.107Historical Redlining Is Associated with Present-Day Air Pollution Disparities in U.S. Cities. (2022). Lane, H., Morello-Frosch, R., Marshall, J. and Apte, J. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 9(4). Academic Research. Climate change will further multiply the inequitable impacts from extreme heat and flooding in EJ areas. To remedy these disparities and build climate resilience, programs and investments should prioritize those communities that have faced chronic government disinvestment and been excluded from decision-making.

Recent State legislation builds upon the sustained advocacy work of EJ communities to evaluate the cumulative impacts of polluting infrastructure. With the 2022 Cumulative Impacts Law, New York is the second state in the nation to pass legislation ensuring that cumulative impacts will be considered in the State’s environmental permitting processes when potentially polluting facilities seek permits in disadvantaged communities.108NY Assembly Bill 1286 of 2023. (2023). New York State Assembly. NYS Government. Decisions driven simply by land costs only compound polluting facilities in EJ communities. State and City agencies will need to balance economics with cumulative impacts in order to move towards a more equitable distribution of environmental burdens. The City will support the State with the Cumulative Impacts Law’s implementation by leveraging existing programs and initiatives, expertise, and data sources to support overburdened communities.

The City is committed to creating a New York where all people can live, work, and play in safe, healthy, resilient, and sustainable environments that will allow them to thrive. This requires working in partnership with EJ communities so that they can meaningfully participate in shaping their places of work, homes, and neighborhoods spaces. New Yorkers organizing for environmental justice have the expertise, the organization, and the drive to create a just city.

Next:The State of Environmental Justice in NYC >>