The findings from this EJNYC Report will inform the forthcoming EJNYC Plan. The Plan will identify citywide and neighborhood-scale initiatives for promoting environmental justice, and it will outline recommendations for embedding equity into the City’s decision-making processes. As the City develops the EJNYC Plan, establishing an overarching set of guiding principles will be necessary to coordinate implementation across City agencies.

This chapter discusses challenges and opportunities with existing environmental decision-making processes, key principles from the EJ movement, and case studies of EJ actions from other local and state governments. The topics addressed in this chapter will inform the development of strategies and actions in the subsequent EJNYC Plan. In addition, City agencies can use this section to improve engagement efforts that seek to meaningfully involve impacted New Yorkers and inform environmental decision-making.

The key findings summarized in this chapter incorporate several types of community engagement and analysis. MOCEJ facilitated work sessions with members of the EJ Advisory Board and EJ Study Contributors to identify opportunities to align existing processes and policies with widely accepted EJ principles, and to facilitate better participation by populations living in EJ Areas. The EJ Advisory Board is a panel of external EJ leaders appointed by the Mayor and City Council to help guide the implementation of Local Law 60. The EJ Study Contributors are representatives from local community-based organizations selected by MOCEJ to provide feedback on EJNYC outputs. In addition, the chapter was informed by a citywide survey developed by MOCEJ and the EJ Advisory Board to better understand New Yorkers’ experiences engaging with the City. Detailed summaries of these inputs may be found in the Appendix: Qualitative Research Methodology.

Challenges and Opportunities

MOCEJ worked with the EJ Advisory Board and EJ Study Contributors to identify opportunities and challenges with existing processes and policies related to environmental decision-making. The following summary reflects opportunities and challenges identified through facilitated working sessions:

Challenges

Top-down Planning & Engagement engagement Participants Want to Be Involved in Planning Processes from the Start, Informing the Vision and Goals of the Project. Current Engagement Processes That Seek Community Input Once a Project

is well-established come across as transactional and inauthentic, limiting residents’ ability to impact projects in a meaningful way. Additionally, this top- down approach underutilizes valuable community knowledge that can help identify key issues or prioritize resources while overemphasizing the perspectives of outside consultants. Cross- agency Coordination: Planning siloed by City agencies prevents coordination of land use and budgeting decisions, both of which greatly impact environmental injustice. Workshop attendees note that future proposals should clearly articulate how the project will advance equity and undo historic disparities.

Priority-setting

Capacity and resource constraints limit agencies’ ability to address all resident concerns. However, workshop attendees note that the priorities that guide agency operations come from City Hall and often lack community perspectives. This perpetuates the frustration that community feedback does not meaningfully inform government action.

Opportunities

Transparency

Clear communication regarding the decisions made thus far and the role of community input and its impact on the project outcomes is essential.

Accessibility

Diverse engagement methods, such as online surveys, canvassing, multi-media advertisement, and partnering with local nonprofits, can help meet community members where they are. This can expand the number of residents engaged and ground projects in a strong understanding of community perspectives. Thoughtful consideration of meeting times, simplifying complex technical and legal documents, and providing translation and interpretation services, on-site child-care, and refreshments can also go a long way.

Capacity-building

Community organizations, advocates, and advisory board members often contribute unpaid labor to EJ work. The City can foster reciprocal relationships with community leaders by investing in EJ advocacy work through dedicated, ongoing support to CBOs; advocacy training programs for emerging leaders; paid liaison positions on Community Boards; and in-house navigators within City agencies.

Decentralization

Innovative public engagement processes can be explored for future City environmental decision- making. Participatory budgeting, a City Council-led process in which community members directly decide how to spend part of a public budget, for example starts with ideas generated by the community, advances to technical experts for further analysis, and then returns to the community for final review. Additionally, empowering the city’s existing network of CBOs to conduct outreach by providing the proper resources and investment can be a model for success.

Key EJ Principles

In recognition of the decades of work from the communities, organizers, and leaders that built the EJ movement, MOCEJ examined key principles and values from the EJ movement and summarized them below. This section will inform the City’s development of the EJNYC Plan.

principles of Ej

One of the most influential and recognizable documents of the EJ movement, the Principles of Environmental Justice, was drafted and adopted by delegates of the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit held on October 24-27, 1991, in Washington DC. The Principles of Environmental Justice represent a multi-cultural, multi-national, and grassroots-defined perspective on the meaning of environmental justice. It is a document that re-defined and re-affirmed what the EJ movement meant going into the 21st century.

These principles are 17 concise statements covering a wide range of topics and values, including protection from nuclear testing and hazardous waste disposal, accountability for past and current polluters, the right to environmental self-determination and participation at every level of decision-making, indigenous rights and treaties, informed consent, the destructive operations of corporations, ethical and responsible use of land and renewable resources, and more. The legacy of these principles is particularly significant; New York City’s own EJ legislation, Local Laws 60 & 64 of 2017, was shaped by several of these principles and the leaders who developed them.

JEMEZ PRINCIPLES FOR DEMOCRATIC ORGANIZING

Between December 6-8, 1996, not long after the adoption to the Principles of Environmental Justice, the Southwest Network for Economic and Environmental Justice (SNEEJ) convened a “Working Group Meeting on Globalization and Trade” in Jemez, New Mexico. This diverse group met with the goal of establishing common understandings amongst themselves and, from that, developed and adopted the Jemez Principles of Democratic Organizing.

The Jemez Principles emphasized bottom-up organizing and the need for the EJ movement to support local organizations best positioned to address environmental injustice. The Principles acknowledge that the strongest movements are not built by individual leaders, but by a community base. One of the most important Jemez Principles is “Let People Speak for Themselves.” This means creating and protecting avenues for those experiencing harm to make their voices heard.

JEMEZ PRINCIPLES OF DEMOCRATIC ORGANIZING

#1 Be Inclusive

#2 Emphasis on Bottom-up Organizing

#3 Let People Speak for Themselves

#4 Work Together in Solidarity and Mutuality

#5 Build Just Relationships Among Ourselves

#6 Commit to Self-Transformation

SPECTRUM OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT TO OWNERSHIP

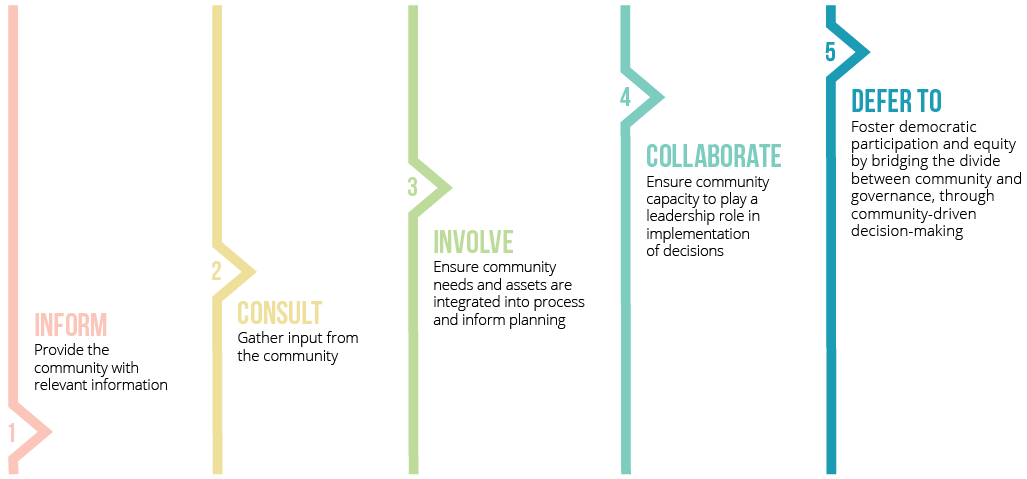

The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership is a tool designed for organizations, such as local governments or CBOs, “to facilitate community participation in solutions development and decision-making.” The Spectrum tool outlines six “phases” of engagement: Inform, Consult, Involve, Collaborate, and Defer To. Each subsequent phase facilitates increasingly strong local democracy and community participation in decision making.

The spectrum tool acknowledges Marginalization as the first phase, representing the status quo of systems which have historically denied low- income communities and communities of color any access to the decision-making process. Beyond Marginalization are “Inform” and “Consult,” which keep communities in the role of absorbing information and providing input to plans or decisions which have largely already been developed and have little room for change. Further along the Spectrum, “Involve” and “Collaborate,” are where power begins to shift towards communities through true decision-making involvement and cross-sector collaboration. By advancing through the Spectrum phases, local governments can achieve the goal of delegating power to community leaders, thereby ensuring that communities inform all stages of decision-making, from planning through implementation.

The final phase of the Spectrum, “Defer To,” describes true community ownership and democratic participation through community-driven decision- making. It bridges the divide between community and governance by ensuring that residents have direct say over how vital resources like housing, food, water, and energy are managed.

BlackSpace is an urbanist collective of Black urban planners, architects, artists, activists, designers and leaders working to protect and create Black spaces. The Manifesto’s values are a useful guide to creating and expanding an organization’s connections and leading work through thoughtful strategies that will keep these connections strong.

The Manifesto emphasizes de-prioritizing hierarchal structures in favor of inclusion and empowerment. It values the development of authentic and high-priority connections over sheer quantity, and highlights seeking connections with marginalized people and communities. Once connections are made, the manifesto advocates for allowing trust to build at whatever speed is necessary, by listening deeply and approaching work with an attitude towards learning and centering the critical expertise of lived experiences.

Before carrying out work, the manifesto reminds organizations to acknowledge relevant histories of both injustice and victories to deepen understandings. It calls for the protection and strengthening of culture, and for the expansion of leadership and capacity-building opportunities. It tells us to imagine and design the future into existence now, center lived experience as an important expertise., and to amplify exceptional and innovative work.

Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership

Adapted from the Movement Strategy Center (MSC)

Citywide Survey

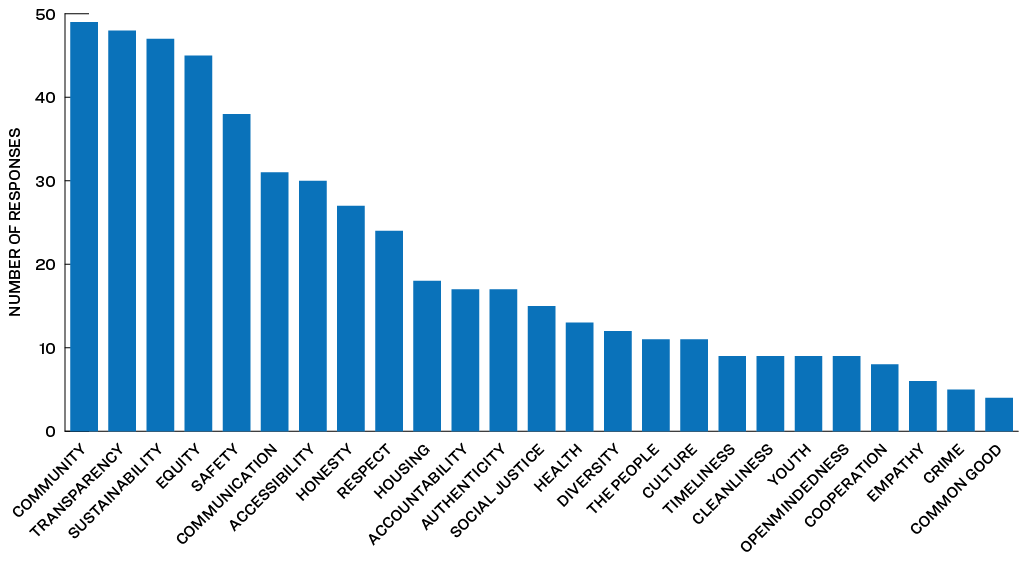

MOCEJ conducted a citywide survey to better understand New Yorkers’ experiences engaging with the City, asking respondents to identify values which should be incorporated into public engagement and environmental decision-making processes. A detailed summary of the survey findings may be found in the Appendix: Qualitative Research Methodology. Notably, respondents provided the following answers when asked about which values should guide the City’s environmental justice actions:

This graph shows the frequency analysis of responses from EJNYC Survey in response to the question: What values should guide City government when asking for the opinions of New Yorkers and making decisions that affect your neighborhoods and communities?

Stakeholder Perspectives

Several members of the EJ Advisory Board and EJ Study Contributors met with MOCEJ to review and discuss the EJ principles and values identified through existing literature and the citywide survey. Several priorities and gaps were identified:

Priorities

- Members reaffirmed several of the values from the survey, specifically transparency, responsiveness, and communication. Members indicated that continued evaluation of the city’s ability to uphold these values is critical.

- Members strongly resonated with the consistent theme of “letting people speak for themselves.” Self-determination is built on true community involvement in decision-making rather than outreach once plans are well-established. As one member noted, the City cannot “center lived experiences” in environmental decision-making if this involvement does not occur.

- Additional values highlighted from existing EJ frameworks include “policy based on mutual respect and free from bias” and “compensation and reparations for EJ victims.”

- Several members spoke positively of the emphasis on process in the BlackSpace Manifesto and the Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership.

Gaps

- Members identified a strong need for a value of accompanying EJ initiatives and meaningful engagement efforts with sufficient funding to meet their stated goals. As reflected in the Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership, investment in community organizing and capacity building is necessary to move towards more effective engagement.

- Members highlighted the importance of City agencies in committing to effective enforcement measures to curb environmental hazards, such as commercial truck idling.

- Other missing values discussed include self- assessment, prioritizing interagency coordination, and open access to information and data.

Highlights of EJ Actions by State and Local Governments

To understand the landscape of EJ action nationally, and to gain knowledge on best practices, considerations, and approaches to environmental justice, MOCEJ reviewed EJ policies and legislation in state and municipal governments outside of New York City. A more detailed summary of this review may be found in the appendix. Notable actions include the following:

Washington Healthy Environment for All (HEAL) Act (2009)

Requires that state agencies incorporate an EJ implementation plan into their broader strategic plans, including agency-specific goals to reduce environmental health disparities, and performance metrics to measure progress

Newark Environmental Justice and Cumulative Impacts Ordinance (2009)

Seeks to measure cumulative impacts of proposed developments through a National Resources Index (NRI) which uses existing geospatial, environmental, and health data to understand site conditions

SB 535 & CalEnviroScreen (2012)

Requires that 25% of moneys from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund and the State’s cap-and-trade program go towards projects benefiting disadvantaged communities. The CalEnviroScreen tool was developed to identify disadvantaged communities that are most affected by multiple sources of pollution, and where people are often especially vulnerable to pollution’s effects.

New Jersey Environmental Justice Law (2020)

Mandates the State to deny permits for new facilities that, as proposed, cause or contribute to adverse cumulative environmental stressors in overburdened communities

New York State Cumulative Impacts Laws (2022)

Regulates the equitable siting of environmental facilities and requires environmental impact statements to state whether the siting of a facility will cause or increase a disproportionate burden on disadvantaged communities

NYSERDA Disadvantaged Communities Stakeholder Services Pool (2022)

Establishes a group of qualified community-based organizations that are representative of the state’s DACs to conduct paid work with NYSERDA staff, including consultation, program and policy input, engagement facilitation, and working group participation

Highlights of Equitable Engagement from City Agencies and City Council

The City has taken steps to meaningfully engage New Yorkers in environmental decision-making. These successes can provide inspiration for future practices that advance environmental justice. Notable examples include:

Community Engagement Framework and Framework Guide

DOHMH, 2017

Developed as part of an internal reform effort to advance health equity goals called “Race to Justice,” this engagement framework can be a useful resource for engagement and strategy development in all City agencies and offices.

Community Planning and Civic Engagement Division

DCP, 2023 – Present

The new division will support all policy and neighborhood planning proposals, as well as discussions on the city’s civic infrastructure to increase and diversify participation in decisions about the future of neighborhoods and the city at large.

Inclusive Engagement Guide

MOPD, 2019

The Inclusive Engagement Guide provides information and resources on how to increase accessibility for New Yorkers with disabilities at public events and meetings. This includes accessibility guidance for the location, written and audio communication materials, digital media materials, and advertising.

NYC Speaks

Deputy Mayor’s Office of Strategic Initiatives, 2021-2022

A public-private partnership between the Deputy Mayor’s Office of Strategic Initiatives, a consortium of philanthropic partners, and a network of community leaders and civic institutions to engage everyday New Yorkers in informing the policies and actions of the Adams administration.

Participatory Budgeting in New York City (PBNYC)

City Council, 2011 – Present

PBNYC gives communities the ability to directly impact the capital budgeting process. The program has grown to include 29 City Council districts, totaling $30 million in capital funding for local improvements to schools, parks, libraries and other public spaces.

The People’s Money

NYC CEC, 2022 – Present

The People’s Money, the first citywide participatory budgeting exercise, allows New Yorkers to decide how to spend $5 million of Mayoral expense funding to address local community needs. Using criteria developed to ensure equity, need, and feasibility, Borough Advisory Committees will work together to determine which projects meet the criteria and will be further developed into proposals that can be implemented.

Place-Based Community Brownfield Planning Areas

NYC OER, 2005 – Present

Place-based Community Brownfield Planning offers $10,000-$25,000 grants to CBOs to conduct brownfield planning at the neighborhood level and to undertake design work or other studies that advance a vacant site towards development. The grants are flexible and can pay for a wide range of services at any stage of a development project prior to construction, including the design of community spaces or evaluating sustainable design interventions.

Language Services Team

MOIA, 2016 – Present

The team provides centralized coordination and delivery of language services for Mayoral Offices including translation, virtual and on-site interpretation, and telephonic interpretation.

Love Your Block Program

Mayor’s Fund to Advance New York City, 2009 – Present

The program provides mini-grants to New York City resident-led groups to transform their neighborhood through a block beautification project while leveraging City services.