Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, policies and activities and with respect to the distribution of environmental benefits.1Ley Local 64 de 2017. (2017). NYC City Council. NYC Government. Fair treatment means that no group of people, including a racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic group, should bear a disproportionate share of the negative environmental consequences resulting from industrial, municipal, and commercial operations or the execution of federal, state or local programs and policies or receive an inequitably low share of resources and environmental benefits.

Prevalent and persistent environmental inequities in New York City create profound economic, social, and health disparities among affected communities. Low-income communities and communities of color are disproportionately impacted by these environmental inequities, due to legacies of discriminatory actions by public and private entities. Achieving environmental justice will require that all New Yorkers have the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards and equal access to the decision- making to have a healthy environment to live, learn, and work.2La justicia ambiental. (n.d.). US EPA. US Government.

The Environmental Justice New York City (EJNYC) initiative represents the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice’s (MOCEJ) implementation of the city’s landmark environmental justice legislation, Local Laws 60 and 64 of 2017. These laws establish foundational requirements to guide the City’s efforts to advance environmental justice in NYC, including the development of the EJNYC Report and EJNYC Mapping Tool, and the forthcoming development of the EJNYC Plan. Together, these efforts will accomplish two objectives: first, to develop a study that provides New Yorkers with an understanding of present-day systemic environmental inequities in the city, and second, to develop a robust plan that effectively advances environmental justice and embeds equity and environmental justice considerations into the City’s decision-making processes.

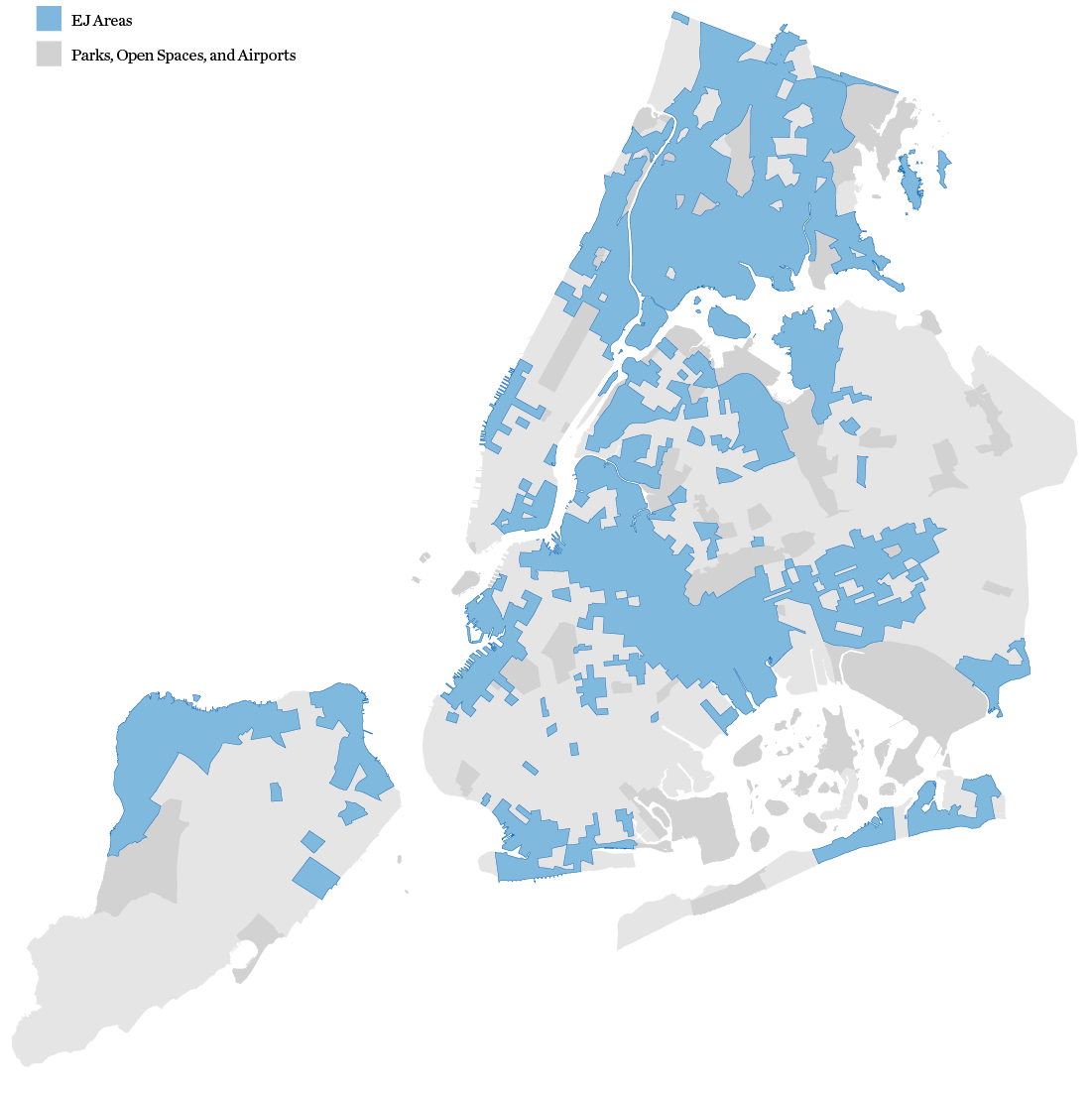

Environmental Justice Areas

In this report, the term “Environmental Justice Area” or “EJ Area” denotes a geographic area that has experienced disproportionate negative impacts from environmental pollution due to historical and existing social inequities without equal protection and enforcement of environmental laws and regulations. The report identifies the city’s EJ Areas using the State’s Disadvantaged Communities (DAC) designation, which is based on a scoring of 45 indicators that describe various sociodemographic and environmental conditions across census tracts.3Draft Disadvantaged Communities Criteria and List Technical Documentation. (2022). NYS Climate Justice Working Group. NYS Government. Based on this designation, EJ Areas account for 44 percent of all New York City census tracts, containing 49 percent of the city’s population. This report also uses the term “Environmental Justice Neighborhood” or “EJ Neighborhood” to denote a geographic area consisting of a majority (greater than 50 percent) of census tracts designated as EJ Areas.

The State of Environmental Justice contains an explanation of why the DAC designation is used in this report and a comprehensive review of the DAC methodology, its limitations, and potential improvements.

New York City’s Environmental Justice Areas

SOURCE: NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, Disadvantaged Communities Criteria, 2023.

Key Findings

The EJNYC Report evaluates a selection of environmental burdens and benefits across the city and between EJ Areas and non-EJ Areas to identify potential disparities. Key takeaways from this analysis include:

- Historically, New York City’s low-income communities and communities of color bore the disproportionate burden of polluting infrastructure while simultaneously experiencing disinvestment in environmental benefits such as parks and natural resources, and solid waste pickup.

Access to Resources

- The impact of redlining (racially discriminatory real estate practices) persists today. Residents living in historically redlined areas are both disproportionately Black and Hispanic or Latino; 67 percent of the total population in historically redlined areas live in EJ Areas today (by comparison, 49 percent of the total NYC population lives in EJ Areas).

- Low-income Hispanic or Latino and Black residents report the highest rates of transit hardship, or inability to afford transit fares, across racial groups. Low-income Bronx residents report the highest rates of transit hardship across the five boroughs.

- New York City has made great progress toward its goals of increasing access to parks and open space, however, there remains a gap in park density: the average amount of accessible park space is 9 acres per 1,000 residents in EJ Areas and 11 acres per 1,000 residents in non-EJ Areas, amounting to a 19 percent deficit for residents in EJ Areas.

- Residents in the Bronx experience both the highest rates of food insecurity and the highest rates of diet-related diseases, such as diabetes and high blood pressure.

Exposure to Polluted Air

- Communities of color are disproportionately exposed to emissions from heavy-duty diesel vehicles due to the location of arterial highways, commercial waste routes, delivery routes, and parking facilities for medium and heavy-duty fleets. These communities also experience observed health disparities, with EJ Areas sustaining the greatest levels of pollution- attributable emergency department visits.

- Stationary sources of pollution, including “peaker” power plants, waste processing facilities, and hazardous waste generators, are disproportionately located in and around EJ Areas.

Exposure to Hazardous Materials

- Hazardous waste generators and storage facilities, including large facilities and chemically intensive small businesses such as auto shops, are predominantly located in EJ Areas. These facilities can emit hazardous materials that can pose adverse health effects to exposed populations.

- In New York City and across the country, there is no complete list of potentially contaminated sites and currently no widespread effort to characterize legacy industrial areas across the city for existing contamination, as these investigations are typically managed on a site- specific basis. This makes it difficult to assess the true distribution of contaminated land in EJ Areas and its impact on residents.

- Federal and State Superfund cleanup sites are established based on environmental and public health concerns. Brownfield cleanup projects are typically driven by the real estate market and area-wide rezonings. As a result, brownfields addressed under local and state government oversight tend to be concentrated in areas that have been rezoned and are undergoing large- scale redevelopment or are localized city-driven projects or infrastructure. The locations of these cleanup sites therefore do not necessarily reflect the distribution of land contamination across the city. There is no public data on cleanup work done privately.

Access to Safe and Healthy Housing

- The legacy of discriminatory housing policies impacts housing conditions for today’s EJ communities. Neighborhoods reporting the most housing maintenance deficiencies and lead paint violations are disproportionately located in historically redlined EJ Areas in the Bronx, Central Brooklyn, and Upper Manhattan, compared to non-EJ Areas.

- Nine out of ten neighborhoods with the highest incidents of three or more maintenance deficiencies in renter households are EJ Neighborhoods.

- Neighborhoods with the lowest rates of air conditioning at home are predominantly EJ Neighborhoods with high heat vulnerability.

Exposure to Polluted Water

- New York City has approximately 14 miles of swimming beaches that serve around 7 million swimmers per year, and many of its waterways are suitable for boating. However, many of the waterways within and surrounding New York City are impaired or stressed and limited for swimming due to a number of factors including water quality, current, and boat traffic.

- Areas of New York City most impacted by stormwater flooding include Southeast and Central Queens, North Staten Island, and Southeast Bronx.

- Black residents are overrepresented among the census tracts with an above average number of confirmed sewer backup complaints.

Exposure to Climate Change

- Most of New York City’s population living in neighborhoods with high heat vulnerability (HVI-5 and HVI-4) live in EJ Areas, particularly in Central Brooklyn, Upper Manhattan, Southeast Queens, and the Bronx.

- The population living in the city’s EJ Areas is disproportionately exposed to flooding due to coastal storm surge, chronic tidal flooding, and extreme rainfall in the current decade. If EJ Areas remain the same, current hazard forecasts for the 2080s suggest that this disproportionate exposure to flooding due to coastal storm surge and chronic tidal flooding could persist.

- Climate change will impact the lives of all New Yorkers, but existing environmental inequities can make residents of EJ Areas more vulnerable. For example, neighborhoods with the lowest rates of air conditioning at home and high heat vulnerability are concentrated in EJ Areas.

Contributing Themes in Environmental Injustice

Structural Racism

Structural racism is rooted in public policy designed for racial segregation. Historically redlined areas have a higher proportion of Black and Hispanic or Latino residents than the city overall, and these areas experience a pattern of disparities in benefits and burdens across multiple EJ issues. For example, Black and Hispanic or Latino residents are more likely to experience health-related housing maintenance deficiencies, transit hardship, and energy cost burden.

Poverty

Poverty often means that marginalized communities have greater exposure to environmental hazards and pollution. Poverty can also restrict access to safe and stable housing, transit, and fresh food. Industries that produce pollution or waste tend to be in low-income areas, further exacerbating the environmental burdens faced by these communities.

Engaging the Public on Environmental Justice

The EJNYC Report also evaluates select City engagement practices to understand how City agencies involve the public in environmental decision-making. This evaluation is supplemented by findings from conversations with New Yorkers in EJ communities and community leaders on the frontlines of the EJ movement. Key takeaways from this evaluation include:

- The City’s efforts to involve the public in environmental decision-making include legally required and voluntary engagement processes. For the public, participating in these processes can be complex, resource and time-intensive, and at times inaccessible, thus limiting the perspectives that are represented. City agencies have used online engagement tools and participatory planning workshops to overcome some of these barriers; however, there are opportunities to expand these efforts in the future.

- The City’s public engagement efforts are often perceived as lacking transparency and not adequately incorporating community feedback. Stakeholder conversations affirmed that improving transparency in engagement processes, collaborating with community-based organizations, and providing resources to support community capacity building and leadership development are effective means of advancing meaningful involvement and environmental justice.

How this Report will Lead to Meaningful Changes

The next step of the EJNYC initiative is the development of a comprehensive citywide environmental justice plan, the EJNYC Plan. Based on the findings of this report, the City will work with environmental justice communities to identify opportunities to advance environmental justice in NYC. In developing this report, the City has begun to identify those opportunities and anticipates exploring them further in the forthcoming EJNYC Plan:

Invest in Environmental Justice Communities

Addressing legacies of environmental injustice requires targeted investments in overburdened and under-resourced areas. Incorporating equity measures into planning, investments, and decision-making will ensure EJ communities get the resources they need to thrive in the face of climate change. Environmental justice investments could include creating new infrastructure that promotes environmental and climate benefits and modernizing existing infrastructure to reduce and eliminate negative impacts.

Integrate Environmental Justice in Agency Decisions Through Climate Budgeting

Climate budgeting can further embed climate and environmental justice considerations into City budgeting to evaluate how budgeting decisions impact long-term climate and environmental justice goals. Embedding environmental justice in this process will help the City align the impact of its investments, identify gaps and opportunities, and increase budget transparency.

Improve Accountability Through Increased Data Transparency and Communication

Transparency in government decision-making is essential to building community trust. Promoting access to information, clear communication channels, and inclusive mechanisms for participation are key to advancing environmental justice priorities. Online data tools, for example, will continue to improve accountability and support residents to advocate for transformational change within their communities.

Coordinate with Permitting and Regulatory Authorities to Embed Equity and Environmental Justice Considerations in the Siting and Permitting of Infrastructure

Embedding equity and EJ considerations in infrastructure siting decisions will help prevent further negative impacts or environmental burdens in EJ communities. The City is committed to working with partners to support policies and regulations, such as New York State’s Climate Act and its forthcoming regulations, that accelerate the investments and benefits of clean energy, climate resilience, and pollution reduction in environmental justice communities.

Explore and Develop New Ways to Collaborate with Environmental Justice Communities

Going beyond traditional engagement, there is opportunity for greater transparency and more meaningful involvement that occurs earlier in decision-making processes. New engagement models, such as the City’s equity-driven Climate Strong Communities approach of initiating work with communities to identify projects for funding opportunities, will help build more meaningful partnerships.

The City recognizes there is substantial work to be done to successfully implement and support citywide environmental justice priorities and is committed to working with the Environmental Justice Advisory Board and EJ communities to identify and establish environmental justice priorities, initiatives, policies, and recommendations through the development of the EJNYC Plan.