Background on Local Laws 60 and 64 of 2017

In 2017, the New York City Council adopted Local Laws 60 and 64, which require the City of New York to assess citywide environmental inequity and develop a plan to incorporate environmental justice into the fabric of City decision-making. The Environmental Justice New York City (EJNYC) initiative represents MOCEJ’s implementation of this landmark environmental justice legislation.

Local Law 60 requires that a citywide study of environmental justice be conducted and that the results of the study be made available to the public and placed on the City’s website. The law also requires the creation of an online environmental justice portal with access to a mapping tool for environmental justice data. This EJNYC Report and the accompanying EJNYC Mapping Tool satisfy these requirements by providing a comprehensive view of the historical and present state of environmental justice in New York City and by providing stakeholders the information and tools to advocate for and advance the best outcomes for impacted communities.

The EJNYC Report and Mapping Tool serve as the foundation for the next major milestone required by Local Law 64: the development of a comprehensive citywide environmental justice plan, the EJNYC Plan. This plan will propose actions to address environmental injustices in communities of color and low-income communities in consultation with EJ communities.

The Environmental Justice Movement

The environmental justice movement emerged out of decades of grassroots organizing, primarily led by people of color who believed that a person’s race or class should not determine their quality of life.4Environmental Justice Timeline. (2022). US Environmental Protection Agency. US Government. Racist historical housing policies contributed to the concentration of polluting and harmful infrastructure in low-income communities and communities of color. In NYC, a legacy of health disparities across racial and socioeconomic lines remains.5, 6, 7, 85: Today’s Health Inequities in New York City Driven by Historic Redlining Practices. (2020). Allard, A., Manko, K., Ford, M.M., Weisbeck, K., and Cohen, L. Primary Care Development Corporation. Academic Research.

6. Zoning Law, Health, and Environmental Justice: What’s the Connection? (2002). Maantay, J. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics.

7. A brief history of redlining. (2021). NYC DOHMH. NYC Government.

8. Air quality and health impacts of diesel truck emissions in New York City and policy implications. (2021). Meyer, M. and Dallmann, For generations, community groups and individuals have advocated for healthy neighborhoods and protection from exposure to environmental and health hazards.9Environmental Justice Timeline. (2022). US EPA. US Government. Now, the City of New York is publishing its study of these impacts on New Yorkers through the lens of environmental justice.

The EJ movement advocates for all people to have the right to equal protection and equal enforcement of environmental laws and regulations, including laws pertaining to human health. The movement recognizes that due to structural racism and class discrimination, communities of color, low-income neighborhoods, and Indigenous Peoples are the most likely to be impacted by harmful exposures, economic injustices, and negative land uses.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16Confronting Environmental Justice: It’s the Right Thing to Do. (1997). Bullard, R., Johnson, G., and Wright, B. Race, Gender & Class.

11. Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States. (1987). United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice. Community Organization.

12. Early-life air pollution and asthma risk in minority children. The GALA II and SAGE II studies (2013). Nishimura, K., et al. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 188(3). Academic Research.

13. PM2.5 polluters disproportionately and systemically affect people of color in the United States (2021). Tessum, C.W., et al. Science Advances, 7(18). Academic Research.

14. Historical Redlining Is Associated with Present-Day Air Pollution Disparities in U.S. Cities. (2022). Lane, H., Morello-Frosch, R., Marshall, J. and Apte, J. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 9(4). Academic Research.

15. Proximity to Environmental Hazards: Environmental Justice and Adverse Health Outcomes. (2010). Maantay, J., Chakraborty, J. and Brender, J. US EPA. US Government.

16. Climate Change and Social Vulnerability in the United States. (2021). US EPA. US Government. At the same time, these historically impacted communities are disproportionately affected by climate change impacts, while generally contributing the least to the climate crisis, and are historically the least likely to benefit from investments to improve the environment.17, 18, 19, 2017. FYs 2022-2026 Strategic Plan. (n.d.). US Department of Justice. Federal Government.

18. Inequity in consumption of goods and services adds to racial–ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure. (2019). Tessum, C., Apte, J., Goodkind, A., et. al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, 116(130). Academic Research.

19. Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence, and Politics (2012). Walker, G. Routledge. Book.

20. Measuring What Matters, Where It Matters: A Spatially Explicit Urban Environment and Social Inclusion Index for the Sustainable Development Goals (2020). Hsu, A. et al. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 2. Academic Research.

Why this Report Now?

The legislative mandate to create this report stemmed from an array of factors. First and foremost, the City acknowledges the determined leadership and immense amount of work that residents have volunteered to fight for the health and safety of their communities. For generations, New York City residents have called for the City to rectify environmental injustices, including removing or remediating lead paint, closing fossil fuel power plants, and providing waterfront access, to name just a few examples.

This report also aligns with the increasing prevalence of EJ action at the state and federal level, which are summarized below. Through the forthcoming EJNYC Plan, the City has the potential to harness some of these emerging resources to benefit New York City’s EJ communities.

- With the Climate Act in 2019, the New York State legislature created a permanent EJ advisory group, the Climate Justice Working Group. One of the nation’s most ambitious climate laws, the Climate Act requires the State to reduce economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions and direct a minimum of 35 percent with a goal of 40 percent of the overall benefits on clean energy and energy efficiency programs, projects, or investments to disadvantaged communities.

- In 2022, New York State voters passed the Clean Water, Clean Air and Green Jobs Environmental Bond Act to support environmental improvements that preserve, enhance, and restore New York’s natural resources and create local green jobs.

- At the federal level, President Biden signed the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law in 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, both of which advance opportunities for environmental and infrastructure improvements and the creation of green jobs.

- The Biden Administration’s Justice40 initiative aims to deliver 40 percent of the overall benefits of certain federal investments to communities that are marginalized and overburdened by pollution. To help define these disadvantaged communities, the Council on Environmental Quality released a Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool in November 2022.

- In addition, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) created a new Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights in 2022 to better advance environmental justice, enforce civil rights laws in overburdened communities, and deliver new grants and technical assistance nationwide.

- The EPA opened applications for the Environmental Justice Government-to- Government (EJG2G) program in January 2023, which provides funding at the state, local, territorial, and tribal level to support government activities that lead to measurable environmental or public health benefits in communities disproportionately burdened by environmental harms.

- The White House’s Climate and Economic Just Screening Tool (CEJST) is used to direct and prioritize federal funding to disadvantaged communities, such as in the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF).

Compounding crises have heightened the need for this EJNYC Report. EJ issues intersect with many other social justice issues faced by communities of color, including over-policing and mass incarceration, inequitable public health outcomes, access to transit and healthy food, and climate justice. As such, addressing EJ issues can support positive outcomes in other areas of concern. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected low-income communities and communities of color, in part due to higher historical exposure to poor air quality.21Inequities in Experiences of the COVID-19 Pandemic, New York City. (2021). NYC DOHMH. NYC Government.

How Was this Report Developed?

This report’s development began with a public scoping process that included thousands of comments from New Yorkers. The City, in partnership with the EJ Advisory Board, conducted this process to ensure that the resulting report would lay the foundation for addressing the issues that EJ communities face. Comments were open to all New Yorkers, though efforts were made to prioritize outreach in the low-income communities and communities of color that have borne the brunt of environmental health issues, the climate crisis, and impacts of the fossil fuel industry. Public input was formalized into a report scope by MOCEJ and the EJ Interagency Working Group, with input from the EJ Advisory Board.

This report’s development involved a mixed methods research approach to provide a comprehensive understanding of New York City’s historical and current EJ issues, informed by data, expert input, and New Yorkers’ day-to-day experiences. This included a review of academic literature, government reports, and materials produced by EJ organizations and advocates in New York City; quantitative and spatial analysis of various EJ indicators; stakeholder conversations from focus groups and interviews; and a targeted survey. Relevant indicators, datasets, and analyses were validated by the EJ Advisory Board and EJ Interagency Working Group. Most of the data used in this report is publicly available, except for a few instances where members of the EJ Interagency Working Group provided non-publicly available data to address discrete information gaps and provide updated datasets.

The purpose of the report was determined to be twofold:

- To study cumulative impacts of environmental burdens affecting low-income communities and communities of color, as well as disparities in environmental benefits. This relates to distributional equity, or programs and policies resulting in fair distribution of benefits and burdens across all segments of a community, prioritizing those with the greatest need.22Equity in Sustainability: An Equity Scan of Local Government Sustainability Programs (2014). Park, A. Urban Sustainability Directors Network. Nonprofit Organization.

- To study the extent to which City processes meaningfully involve and take direction from New Yorkers, particularly those in EJ communities. This relates to procedural equity, or inclusive, accessible, and authentic engagement and representation in processes to develop or implement programs and policies.23Equity in Sustainability: An Equity Scan of Local Government Sustainability Programs (2014). Park, A. Urban Sustainability Directors Network. Nonprofit Organization.

Furthermore, MOCEJ, in partnership with the EJ Interagency Working Group, developed an inventory of City programs, policies, and processes to be evaluated in this report. Policy evaluations were sensitive to the different forms of equity, including distributional (ensuring programs and policies result in fair distributions of benefits and burdens across all segments of a community, prioritizing those with highest need); and procedural (inclusive, accessible, authentic engagement and representation in decision- making processes regarding programs and policies).24Environmental Justice Primer for Ports: Defining Environmental Justice. (2023). US EPA. US Government. Those that met the criteria developed in the public scoping process were evaluated to determine the extent to which they benefit EJ communities and provide opportunities for meaningful public involvement. These findings are included in The State of Environmental Justice in New York City এবং Engaging the Public on Environmental Justice. For more detailed information on the various research methodologies used to develop this report, please see the methodology statements in the Appendix.

This EJNYC Report is also accompanied by the EJNYC Mapping Tool, which contains a series of interactive maps with information on EJ indicators citywide. The EJNYC Mapping Tool is designed to equip New Yorkers and cross-sectoral stakeholders with the information necessary to advocate for and make more informed decisions about EJ in New York City. The tool consists of six maps, grouped thematically to reflect the analysis in the EJNYC Report and offering users the ability to explore and analyze a wide range of data layers from City, State, and federal agencies through a user-friendly interface. The mapping tool also allows users to analyze and compare datasets, offering the ability to overlay multiple data layers to identify spatial patterns and relationships to understand the intersections between various environmental and social factors. Users can download the underlying data for additional analysis. The EJNYC Report and Mapping Tool were prepared from Summer 2022 through Winter 2024 and represent the latest data available at the time.

EJNYC INITIATIVE PROCESS AND TIMELINE

What are the Contents of this Report?

This report begins with a History of Environmental Injustice and Racism in New York City to ground the findings in their root causes and further understanding of government’s role in producing environmental disparities across racial and socioeconomic groups.

The State of Environmental Justice analyzes EJ issues affecting New York City across impact areas including but not limited to air quality, housing quality, and access to resources. This chapter focuses on distributional equity issues, analyzing the ways environmental benefits and burdens are distributed across EJ communities as compared to the rest of New York City. For example, is air quality significantly worse in EJ communities? Each topic area is accompanied by maps that highlight disparities between EJ and non-EJ communities, case studies on community- led EJ initiatives, spotlights on related City programs and policies, and feedback from the stakeholder engagement that was conducted to inform this report.

Engaging the Public on Environmental Justice focuses on procedural equity, analyzing formal and informal methods of engagement in the City’s environmental decision-making processes, supplemented by community perspectives from focus groups, interviews, and surveys. This chapter analyzes planning and policy-making processes, such as the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP).

The final chapters of the report look ahead, exploring what it might look like for the City to prioritize and operationalize EJ principles in decision-making processes, policies, and programs. These chapters are supplemented by case studies from other governments across the country that address EJ issues, as well as implementation principles for City agencies informed by values from the EJ movement and feedback from stakeholder engagement. The report closes with an overview of the accompanying mapping tool and a description of this report’s relationship to the forthcoming EJNYC Plan.

What is the Scope of this Report?

This report is a snapshot of EJ issues experienced today in New York City. Specific strategies and actions for addressing EJ issues will be elucidated in the subsequent EJNYC Plan. While the issues discussed in this report often transcend jurisdictional boundaries, the findings and the subsequent plan focus on the sphere of influence of City government. In some cases, collaboration with the State and federal government may be necessary to implement the recommendations that emerge from the forthcoming EJNYC Plan.

Jurisdictional interaction in New York City creates a complex regulatory environment for residents and regulators alike. Addressing EJ issues requires careful coordination across levels of government. For example, the NYC Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) manages the city’s drinking water supply, sewage treatment, and stormwater management; the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) monitors wetlands and administers the State Pollution Discharge Elimination System (SPDES) permitting; and at the federal level, the US EPA administers the Clean Water Act and the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) regulates dredging, the discharge of dredged or fill material, and the construction of certain structures in waterways and wetlands.

Additional Qualitative Research Conducted for the EJNYC Report

Targeted qualitative research was conducted for the EJNYC Report in the form of focus groups, key stakeholder interviews, and a survey to better understand issues affecting EJ communities and the ways communities have self-organized to address these issues. To promote inclusiveness in public processes, which have historically favored well-resourced individuals and organizations that can more easily afford to donate their time, all participants in the targeted focus groups and interviews were compensated for their time.

A key takeaway from this research effort is that New York City residents have undertaken tremendous efforts and achieved many environmental justice victories. Participants in the focus groups identified several impactful initiatives spearheaded by EJ organizers across the City, including a community garden in Edgemere, Queens, that addresses food access issues, and a high school EJ group advocating for tree corridors in Washington Heights, Manhattan.

The scope of stakeholder outreach conducted for this report was limited, so to collect feedback informed by experience at the forefront of the EJ movement, engagement focused on residents experiencing the brunt of EJ issues in New York City and EJ leaders citywide. The stakeholder feedback is not representative of all EJ communities, and the City will conduct additional engagement for the development of the EJNYC Plan.

The findings from the qualitative research are incorporated throughout the report, particularly in Engaging the Public on Environmental Justice.

“It doesn’t matter if you are not biologically related to your neighbors down here, but everybody really takes care of each other.”

—FOCUS GROUP PARTICIPANT

Focus Groups

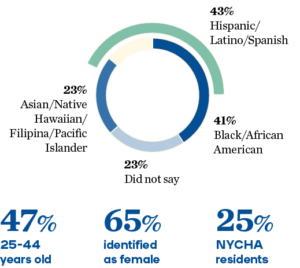

Facilitators convened a diverse group of EJ community members, who were recruited primarily through referrals by community-based organizations, to evaluate relevant City programs, policies, and public engagement protocols in environmental decision-making. Twenty-two New Yorkers participated in the focus groups, representing all five boroughs and various EJ communities to speak about a cross-section of EJ issues. Though the overall number of participants was small, they represented a range of racial and ethnic identities, ages, and gender identities:

“A basic tenet of environmental justice is that we speak for ourselves… Any design or strategic plan must begin with the work already being done by [environmental justice organizations].”

—EJ STAKEHOLDER

Interviews

Leaders of grassroots EJ organizations were interviewed about their direct experience organizing in EJ communities and interacting with City government. Participants shared information on their work, identified the most pressing EJ concerns in their communities, and discussed perceptions of City environmental policies and programs. Interviewers reached 16 stakeholders across all five boroughs and touched on a wide range of EJ issues.

Survey

The survey reached a broader audience, collecting feedback from the residents of EJ communities on civic participation in environmental decision- making, receiving a total of 992 responses.

“The City has identified several opportunities to advance environmental justice in NYC through the comprehensive and collaborative first phases of the EJNYC initiative.”

The private sector also plays a role in both exacerbating and addressing some of the issues outlined in this report. Private entities and individuals may exacerbate EJ issues by not complying with environmental regulations. There are documented examples of private actors illegally dumping waste and hazardous materials, creating illegal sewer connections, and other unlawful actions. Even when complying with environmental regulations, private actors can contribute to environmental degradation and loss of green space. As such, addressing environmental issues often relies on private sector participation, in many cases through the cleanup of brownfield sites, defined as former industrial or commercial sites where future use is affected by real or perceived environmental contamination. Almost all brownfield cleanup in the city is undertaken by private developers who incorporate site cleanup into redevelopment (even when they themselves did not cause the contamination). Partnership with and cooperation from the private sector will continue to be necessary to address many EJ issues in New York City, where the free market largely drives investment and disinvestment in certain communities.

The City recognizes the urgency of EJ issues and looks forward to working directly with EJ communities to turn the findings of this report into a plan for action that will improve quality of life for those bearing the brunt of the most pressing environmental issues.

How will this Report Lead to Meaningful Changes?

The City of New York is committed to advancing environmental justice and addressing systemic inequities. Disadvantaged communities have borne the brunt of pollution, exposure to hazardous materials and pollution, and insufficient access to resources. The Mayor’s Office of Climate & Environmental Justice (MOCEJ), Environmental Justice Interagency Working Group (IWG), and Environmental Justice Advisory Board (EJAB) will build on this EJNYC Report and Mapping Tool by launching a community-based process to develop the EJNYC Plan, which will propose strategies and initiatives to address EJ issues, including those studied in this report.

The forthcoming EJNYC Plan will outline what the City will do to address the cumulative impacts of local EJ issues and improve the quality of life and wellbeing for communities experiencing longstanding and disproportionate burdens. The plan will provide guidance on incorporating EJ priorities into City decision-making, identify possible citywide initiatives that will promote EJ, and provide recommendations for City agencies. Recommendations in the EJNYC Plan may include policies designed to close the gap on environmental health disparities, expand environmental benefits and investments to communities, and ensure protection from environmental and health hazards and access and inclusion to planning and decision- making processes.

The policy opportunities below represent some of the City’s key opportunities to advance transformative change for environmental justice in the five boroughs. These opportunities and others will be explored further through the forthcoming EJNYC Plan.

Invest in Environmental Justice Communities

Historically, New York City’s low-income communities and communities of color have been overburdened by polluting infrastructure and decades of disinvestment. Tackling the resulting inequities requires deliberate and targeted investments in critical resources and environmental benefits for those most in need and vulnerable to climate change.

The federal and New York State government have made unprecedented commitments to directing investments in disadvantaged communities. The federal Justice40 initiative aims to direct 40 percent of overall benefits of certain federal programs to disadvantaged communities as identified with the White House’s Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST). New York State’s Climate Act requires that state agencies, authorities, and entities direct a minimum of 35 percent with a goal of 40 percent of the overall benefits on clean energy and energy efficiency programs, projects, or investments in the areas of housing, workforce development, pollution reduction, low-income energy assistance, energy, transportation, and economic development go to disadvantaged communities. In addition to the State’s commitment to invest in disadvantaged communities, the NYS Commission to Study Reparations and Racial Justice is analyzing the lasting impacts of slavery to recommend ways to address historical inequities. The City applauds these historic policies and will work to establish local investment commitments that directly benefit EJ communities and address local EJ concerns.

The City will build on this EJNYC Report and Mapping Tool by launching a community-based process to develop the EJNYC Plan, which will propose strategies and initiatives to address EJ issues”

The City will also build on successful components of existing equity-driven programs such as DOT’s Priority Investment Areas and DEP’s Lead Service Line Replacement Program. In addition to scaling existing equity initiatives, the City will work across agencies to develop new strategies and processes to further institutionalize EJ investments.

Integrate Environmental Justice in Agency Decisions Through Climate Budgeting

Climate budgeting is a key component of the City’s ambitious climate agenda. This innovative approach integrates science-based climate considerations into municipal budget decisions, evaluating the alignment of budgeting decisions with long-term climate priorities.

The City’s climate budgeting initiative was announced in 2023 in PlaNYC: স্থায়িত্ব সম্পন্ন করা and, as of the release of this report, is in its first year. The Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) will produce annual progress reports, which will include tracking progress on environmental justice over time. This initiative will foster public accountability and transparency and can serve as a model for integrating equity in City spending.

How this Report will Lead to Meaningful Changes

Improve Accountability Through Increased Data Transparency

Transparency in government decision-making is essential to maintaining the public’s trust. Many stakeholders consulted through this study echoed longstanding calls for increased transparency and data accessibility. Promoting access to information, clear communication channels, and inclusive mechanisms for participation are key to advancing environmental justice.

In addition to committing to progress reporting through the climate budgeting initiative, the City is leveraging online data tools to democratize access to data. Resources like the EJNYC Mapping Tool and the Equitable Development Data Explorer equip residents with valuable knowledge related to their built and natural environments, allowing them to more easily identify local inequities, advocate for community solutions, and promote greater accountability. The City will develop new and diverse opportunities to work with cross-sectoral stakeholders to improve data and information sharing. These and many other efforts will be further developed in the EJNYC Plan.

Coordinate with Permitting and Regulatory Authorities to Embed Equity and Environmental Justice Considerations in the Siting and Permitting of Infrastructure

Environmental justice communities are historically overburdened by the siting of polluting infrastructure such as power plants, waste transfer stations, and congested highways. Such infrastructure can perpetuate social, climate, and environmental inequities by compounding existing burdens in EJ communities such as lower access to greenspace and healthy foods. The City seeks to leverage its partnerships with public authorities across all levels of government to ensure equity and environmental justice are central to future infrastructure siting decisions.

The New York State Cumulative Impacts Law provides a strong foundation for this; it prevents the approval and re-issuing of permits for actions that would increase disproportionate and/or inequitable pollution burdens on disadvantaged communities. This policy is a blueprint for a more equitable distribution of infrastructure benefits and burdens. The City will actively engage with relevant permitting and regulatory authorities to implement this law’s principles.

Explore and Develop New Ways to Collaborate with Environmental Justice Communities

EJ communities have long advocated for their voices to be heard in decision-making that impacts their neighborhoods. While the City has made progress on meaningful engagement, stakeholders continue to advocate for greater transparency and more meaningful involvement that occurs earlier in decision-making processes. Stakeholders identified opportunities for the City to help EJ advocates overcome resource challenges through capacity- building, training, and City agency liaisons.

The City aims to expand existing efforts and explore new models for collaboration to foster meaningful involvement in decision-making. In recent years innovative programs have emerged to meaningfully involve EJ communities, and these strategies can be scaled and replicated across agencies to institutionalize collaborative frameworks. The City is proactively advancing community partnerships through initiatives like the Climate Strong Communities (CSC) Program, a citywide strategy targeting multi-hazard resiliency projects in historically marginalized and at-risk communities. This approach emphasizes collaborative planning that involves City agencies, neighborhood groups, and residents to ensure investments align with community priorities. The Department of Housing Preservation (HPD) similarly champions community involvement through its Neighborhood Planning program. Through Community Visioning Workshops, HPD works directly with residents to co-create strategies for delivering high-quality affordable housing in a manner that aligns with local priorities and promotes equitable, diverse, and livable neighborhoods.

In Addition to the EJNYC Plan, this Report May Inform Related Efforts, Including but Not Limited To:

PlaNYC

A series of climate action plans released by New York City, pursuant to Local Law 84 of 2013. The latest action plan released in 2023, PlaNYC: Getting Sustainability Done, builds on the prior four plans while it faces the challenges and seizes the opportunities that are specific to today. It is grounded in a comprehensive understanding of climate change impacts in the city as they are happening, as well as a more complete picture of our GHG footprint.

পাওয়ারআপ এনওয়াইসি

A collaborative, year-long energy planning study to catalyze City government action to clean up our air, make energy bills more affordable, create good-paying jobs, and create opportunities for local, community-owned clean energy.

জলবায়ু শক্তিশালী সম্প্রদায়

An initiative to develop equitable resiliency projects focused in areas of New York City where residents face disproportionate risks from climate change.

Energy Cost Burden Study

A 2019 report which assesses the extent to which low-income NYC families are energy cost burdened, meaning they spend more than 6 percent of their pre-tax income toward their energy bills, and proposes policies that can lower the outstanding burden. An update to this analysis is being developed by MOCEJ and NYC Opportunity.

Glossary of Terms

Disadvantaged Communities (DACs) Communities that bear burdens of negative public health effects, environmental pollution, impacts of climate change, and possess certain socioeconomic criteria, or comprise high-concentrations of low- and moderate- income households, under the New York State Climate Act.

Disproportionate Significantly higher and more adverse health and environmental effects on EJ communities, or other communities if stated otherwise.

EJNYC Mapping Tool Local Law 60 of 2017 requires the EJ Interagency Working Group to make publicly available online an interactive map showing the boundaries of EJ Areas within the City and the locations of sites, facilities and infrastructure which may raise environmental concerns.

EJNYC Plan Local Law 64 of 2017 requires the EJ Interagency Working Group to develop a comprehensive Environmental Justice Plan that provides guidance on incorporating EJ concerns into City decision-making, identifies possible Citywide initiatives for promoting EJ and provides specific recommendations for City agencies to bring their operations, programs and projects in line with EJ concerns. The IWG must update the EJNYC Plan every five years. The bill also requires the EJ Advisory Board to closely consult the EJ Interagency Working Group during development of the EJNYC Plan. Development of the Plan will follow the release of this EJNYC Report.

EJNYC রিপোর্ট This report satisfies the requirement to produce an EJ study defined by Local Law 60 of 2017, which shall identify the locations and boundaries of EJ Areas within the City, describe environmental concerns affecting these areas, and identify data, studies, programs and other resources that are available and that may be used to advance EJ goals. The bill requires the EJ Interagency Working Group to issue recommendations for legislation, policy, budget initiatives and other measures to address environmental concerns affecting EJ communities.

Environmental Benefit Access to open space, green infrastructure and, where relevant, waterfronts. Environmental benefits also include the implementation of environmental initiatives, including climate resilience measures, as well as grants, subsidies, loans, and other financial assistance relating to energy efficiency or environmental projects.

Environmental Burden An environmental factor that has the potential to negatively impact New Yorkers’ health, well-being, quality of life or enjoyment. Examples include stationary sources of air pollution, hazardous waste, housing with maintenance deficiencies, and lack of public open space.

Environmental Justice (EJ) The principle that all people, regardless of race, disability, age, or socioeconomic background, have a right to live, work, and play in communities that are safe, healthy, and free of harmful environmental conditions.

Environmental Justice Advisory Board (EJAB) Local Law 64 of 2017 established an Environmental Justice Advisory Board comprised of external environmental justice leaders (advocates, academics, and public health experts) to advise the City as it implements these laws and to bring this work to New Yorkers through public hearings and other forms of engagement. The EJ Advisory Board’s charge is to ensure the work is grounded in the lived experiences of New Yorkers in the city’s EJ communities.

Environmental Justice Area (EJ Area) This report defines EJ Areas as census tracts that meet the Disadvantaged Communities (DAC) designation established by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. This designation was developed by the Climate Justice Working Group, as mandated by the Climate Act, and is used to identify frontline and otherwise underserved communities that stand to benefit from New York State’s historic transition to cleaner, greener sources of energy, reduced pollution and cleaner air, and economic opportunities.

Environmental Justice Community (EJ community) This term is used throughout the report to generally describe populations that have experienced and/or currently experience EJ issues.

Environmental Justice Interagency Working Group (IWG) Implementing body established to deliver on the requirements of the City’s Environmental Justice Laws. Members of the EJ Interagency Working Group were selected based on their expertise in environmental policy and data analysis, and their agencies’ contribution to the local environment as well as the health of New Yorkers.

Environmental Justice Neighborhood (EJ Neighborhood) A geographic area consisting of a majority (greater than 50 percent) of census tracts designated as EJ Areas.

New York State Climate Act (CLCPA) or Climate Act The New York State legislature passed the Climate Act (known originally as the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act) in 2019. The Climate Act created a permanent EJ advisory group, the Climate Justice Working Group and requires the State to reduce economy- wide greenhouse gas emissions and ensure that at least 35 percent of clean energy and energy efficiency program benefits are distributed to disadvantaged communities.

Structural Racism Racism is a system of power and oppression that assigns value and opportunities based on race and ethnicity; structural racism is racial bias across institutions, including government agencies, and society.

Next:History of Environmental Injustice and Racism in NYC >>