Spatial Analysis Methodology

Overarching Analyses

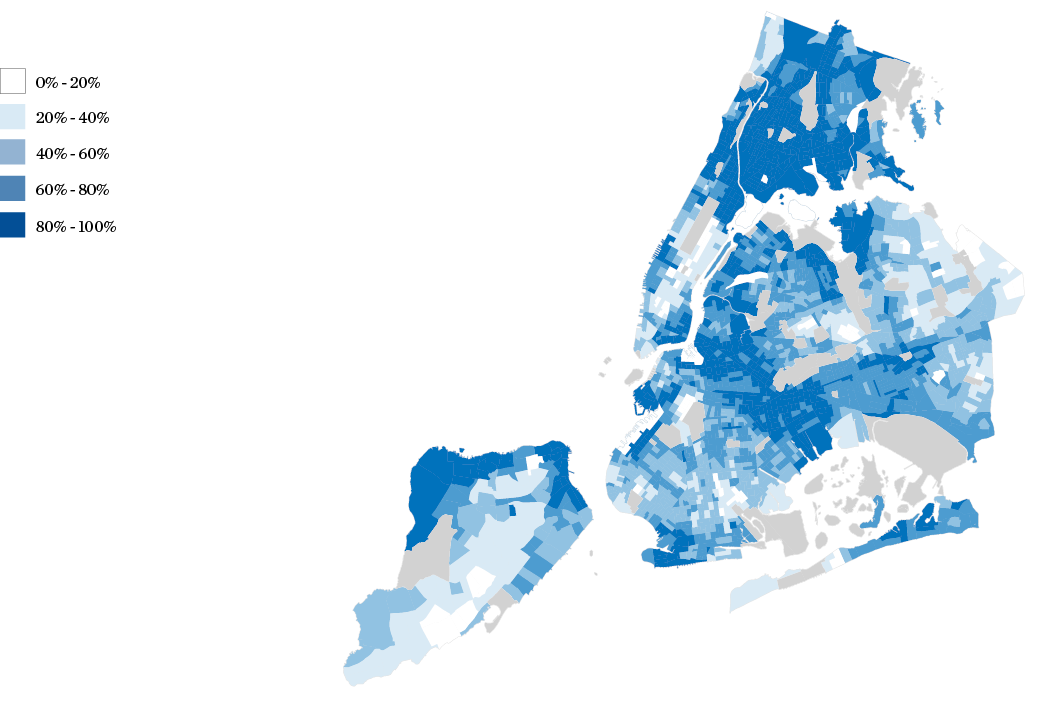

Percent of Nta Population Living in an EJ Area

Data sources: NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, Disadvantaged Communities Criteria, 2023.

Methodology notes: To estimate the percent of the NTA population living within an EJ area the total NTA population was calculated and divided by the total population living in census tracts designated as disadvantaged communities by NYS Department of Environmental Conservation.

Cross Walk of 2020 Acs to 2010 Census Tract Geographies

Data sources: B03002 & C17002, ACS 2021 5 Year Estimates; IPUMS NHGIS, University of Minnesota, www.nhgis.org.

Methodology notes: NYS Department of Environmental Conservation Disadvantaged communities Criteria uses 2010 census tract geographies. To use the latest American Community Survey (ACS) estimates for population and demographics within these older geographies, a geographic crosswalk was used.

National Historic GIS (NHGIS) 2020 Census Blocks to 2010 Census Tracts geographic crosswalk files were used to estimate 2021 ACS 5 Year estimates within 2010 Census Tract geographies. These crosswalks provide interpolated population-based weights to estimate the populations within non overlapping geographies between years. For the greatest accuracy of these adjustments census block estimates for 2021 ACS data were tabulated within 2010 census tracts.

Access to Resources

Population weighted average density of parks per NTA (accessible acreage per

1000 residents)

Source: NYC Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks), Parks Properties, 2023. American Community Survey, 2017-2021 5 Year Estimates. NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, Disadvantaged Communities Criteria, 2023. NYC Department of City Planning (DCP), 2010 Neighborhood Tabulation Areas, 2010.

Methodology notes: The population weighted average number of accessible park acres per 1000 residents were calculated at the census tract level by summing all the acreage for all parks within 1/8 of a mile of the boundary of each census tract. This value was then aggregated to the NTA level (using a population weighted average). This approach takes into account parks that are accessible to a neighborhood even if they are technically outside of its borders (eg. Central Park for the Upper East Side). To estimate accessible park acreage per 1000 residents at the NTA level the population weighted average of accessible acres for each census tract within the NTA was taken.

Tree Canopy Coverage

Source: University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Laboratory New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications (NYC DoITT), Applied Geographics (AppGeo), Quantum Spatial, Land Cover Raster Data (2017) – 6in Resolution.

Methodology notes: Tree canopy coverage per NTA was calculated by determining the percent of the NTAs total area occupied by areas categorized as ‘tree canopy’ in the latest high resolution public remote sensing scan of NYC (LiDAR).

Historically Redlined Neighborhoods (d – Hazardous) and EJ Areas

Source: NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, Disadvantaged Communities (DAC) Criteria, 2023. Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al., “Mapping Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers.

Methodology notes: Areas that were historically redlined were mapped based on digitized historical Home Owner’s Load corporation maps, ‘D’ or ‘hazardous’ ratings areas were considered for inclusion. Redlined areas were intersected with census tracts to estimate demographics for residents within these areas. For census tracts that did not fall entirely within the historically red lined area populations and demographics were estimated based on the proportion of the census tract area within the redlined zone.

Alcohol and Tobacco Vendors by Nta

Source: New York State Liquor Authority, Liquor Authority Current List of Active Licenses, 12/01/2022 snapshot, and New York State Department of Health, Active Tobacco Retailer Map, 12/01/2022 snapshot.

Methodology notes: Records for tobacco and liquor licenses were geocoded based on their recorded address within state license records. Records were then aggregated to the census tract and NTA level based on their location.

Transit Access

Source: MTA Subway Stations, 2022, and Newman Library of Baruch College GIS Lab, NYC Bus Stops 2020.

Methodology notes: To estimate the population with limited access to subway transit half mile buffers were calculated around each MTA subway station. These zones were intersected with census tracts and populations and demographics were estimated based on the proportion of the census tract area falling outside of these transit access zones. The same process was used for access to bus stops, with a quarter mile buffer distance used.

Sbs Network Coverage

Source: MTA, NYC Bus Stops September 2023, 2023.

Methodology notes: Bus stop data was gathered using the methodology original used by Newman Library of Baruch College GIS Lab and August 2023 bus data from the Data Feeds from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). To estimate the population with limited access to SBS stops quarter mile buffers were calculated around each MTA SBS stop. These zones were intersected with census tracts and populations and demographics were estimated based on the proportion of the census tract area falling outside of these transit access zones.

Bike Network Coverage

Source: NYC DCP, LION Single Line Street Base Map, Release 22C, 2022.

Methodology notes: Bike network coverage was calculated as the total distance of bike lanes within each NTA divided by the total roadway distance (excluding highways).

Source: Department of Transportation (DOT), New York City Bike Routes, 2022.

Methodology notes: Protected bike network coverage was calculated as the total distance of protected bike lanes within each NTA divided by the total roadway distance (excluding highways).

Exposure to Polluted Air

Air Pollution Levels by Nta (ozone, Pm2.5, Nitric Oxide, Black Carbon)

Source: NYC DOHMH, New York City Community Air Survey (NYCCAS) Air Pollution Raster, Black Carbon, 2022.

Methodology notes: Uses the latest available year as input (Dec 2019-Dec 2020) for annual average predicted levels of PM2.5, ozone, nitric oxide and black carbon. In order to summarize at the census tract level, raw raster data source was converted to points. In cases where multiple points intersect a census tract, an average of the values was taken; in cases where no points intersect a tract, the values of the nearest point was assigned to the tract. To evaluate NTA-level values for pollution population-weighted averages were taken for census tracts within each NTA.

Areas Within 1 Mile of Power Plants and Facilities with Title V Permits

Data Sources: Energy Information Administration, Form EIA-860, 2021. New York State, Department of Environmental Conservation, Title V Emissions Inventory, 2020 facilities.

Methodology notes: This analysis highlights all areas within 1 mile of all facilities with Title V permits (2020) and power plants with greater than 1 MW operating capacity (in operation in 2021). Buffers of 1 mile were created and intersected with census tracts to estimate demographics for residents within these areas. For census tracts that did not fall entirely within the 1mile area surrounding polluting facilities population was estimated based on the proportion of the census tract area within the buffer.

Neighborhoods with the Greatest Vehicle Traffic Density

Data sources: NYS DOT, AADT Annual Volume of Vehicle Travel, 2019.

Methodology notes: The population weighted average of AADT for all road segments intersecting each NTA was taken to obtain neighborhood level estimates for the level of vehicle traffic density.

Neighborhoods with the Greatest Volume of Indoor Environmental Air Complaints

Data sources: New York City Office of Technology and Innovation, 311 Service Requests “Indoor Air Quality” complaints for 2022.

Methodology notes: The total number of 311 requests from 2022 of the type “Indoor Air Quality” were geocoded based on latitude and longitude and summed by NTA. Values are expressed in complaints per 1000 residents based on ACS population estimates for each NTA.

Exposure to Hazardous Materials

Toxic Release Inventory Facilities

Source: US EPA, TRI Basic Data Files, 2022.

Method notes: The total number of Toxic Release Inventory facilities and quantity of total releases were calculated at the NTA level.

Automotive Body, Paint and Interior Repair and Maintenance, and Dry Cleaning Services Facilities

Source: NYC Department of Environmental Protection, “Right-to-Know (RTK) Program”, 2022

Method notes: The total number of facilities categorized as automotive repair, automotive body, paint and interior repair and maintenance, and dry cleaning services were calculated at the community district level.

Cleanup Sites

Source: NYC OER, OER Cleanup Sites, 2022. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Remediation Sites, 2022. Environmental Protection Agency, Superfund Site Boundaries.

Methodology notes: To obtain a count of clean up sites per census tract all NYS Remediation sites were included and the counts of NYC OER sites, includes all sites in the E-Designation program where cleanup is required. This includes Voluntary Cleanup Program sites if the site also is subject to the E-Designation program.

Solid Waste Management – Average Daily Throughput

Source: DSNY, Annual Report on the Implementation of New York City’s Waste Equity Law, 2022.

Methodology notes: This analysis sums the average daily throughput of municipal solid waste (MSW) and construction and demolition debris (C&D) for material transfer stations subject to LL152 and the MSW transfer stations operated by DSNY. It does not include fill material transfer stations permitted by DSNY and other transfer stations that are not covered by LL152.

Access to Safe and Healthy Housing

Utility Access and Affordability

Source: American Community Survey, 2017-2021 5 Year Estimates. Mayor’s Office of Economic Opportunity.

Methodology notes: Top 25 percent of PUMAs in terms of the percent of households who are utility burdened were calculated based on summarized microdata analyzed by the Mayor’s Office of Economic Opportunity.

Health-related Design and Maintenance Issues

Source: NYC HPD, New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey, 2017.

Methodology notes: This map shows the percent of renter households who report three or more maintenance deficiencies by subboro area with DAC areas overlaid. Maintenance deficiencies include: 1) additional heating required in winter; 2) heating breakdown; 3) cracks or holes in interior walls, ceilings, or floors; 4) presence of rodents; 5) presence of broken plaster or peeling paint; 6) toilet breakdown; 7) water leakage into unit.

Lead Paint Violations

Source: NYC HPD, Code Violations, 2023.

Methodology notes: The number of lead paint-related housing maintenance code violations were summed across NTAs to calculate both the highest total incident count per area as well as the highest population normalized count per area.

Rates of Internet Access in EJ and Non-ej Areas

Source: ACS 2021 5-year estimates

Methodology notes: The population weighted average percent of households without access to the internet (home or cellular) was calculated for EJ census tracts and non-EJ census tracts based on ACS estimates of population and rates of internet access at the census tract level.

Ntas with the Highest Number of Lead Service Lines

Source: Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), Lead Service Line Location Coordinates, 2023.

Methodology notes: To calculate the service line-normalized number of lead service lines, service line records (available at the parcel record level) were filtered based on the material type listed. Lead service line records were joined to census tracts based on the centroid of the service line geometry, census tract totals were then aggregated to NTAs. Records categorized as ‘potential lead’ were considered to be possible lead service lines. This value was divided by the total number of service line records with either ‘not lead’ or ‘unknown’ material types for each census tract.

Noise Complaints

Source: New York City Office of Technology and Innovation, 311 Service Requests “Noise” complaints, 2022.

Methodology notes: The total number of 311 requests from 2022 of the type “Noise” were geocoded based on latitude and longitude and summed by NTA

Exposure to Polluted Water

Confirmed Backup Sewer Complaints

Source: NYC Department of Environmental Protection, 2022.

Methodology notes: The total number of 311 complaints in 2022 of the type “Sewer Backup” and “confirmed” were geocoded based on latitude and longitude and summed by NTA.

Water Quality Assessment for Recreational Use and NYC Parks “waterfront Facilities”

Source: NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Water, Bureau of Water Assessment and Management,” 2019. NYC Parks, “Parks Properties,” 2022.

Methodology notes: Waterbodies are mapped according to their water quality assessment for recreational use. NYC Parks properties with a type category field equal to “Waterfront Facilities” are mapped.

Exposure to Climate Change

انتہائی گرمی

Source: New York City Department of Health, Environment & Health Data Portal. Climate data. Heat vulnerability index (NTA), 2023.

Methodology notes: Percents of population within EJ areas for each HVI value were calculated by intersecting the census tracts with the HVI NTAs. Populations were estimated based on the proportion of the census tract area falling within or outside each NTA.

Coastal Storm Surge

Source: Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice (MOCEJ),ixFormerly the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability (OLTPS) Sea Level Rise Maps (2080s 100-year Floodplain), 2021. American Community Survey, 2017-2021 5 Year Estimates.

Methodology notes: Population and demographics of residents within the floodplain were calculated by intersecting the coastal flood plain with census tracts. Populations and demographics were estimated based on the proportion of the census tract area falling within or outside of the floodplain.

Source: Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice (MOCEJ), Sea Level Rise Maps (2020s 100-year Floodplain), 2021. American Community Survey, 2017-2021 5 Year Estimates.

Methodology notes: Population and demographics of residents within the floodplain were calculated by intersecting the coastal flood plain with census tracts. Populations and demographics were estimated based on the proportion of the census tract area falling within or outside of the floodplain.

دائمی سمندری سیلاب

Source: New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC), Future Tidal Flooding Due to Sea Level Rise, 2018. American Community Survey, 2017-2021 5 Year Estimates.

Methodology notes: Population and demographics of residents within the sea level rise were calculated by intersecting the future high tides with census tracts. Populations and demographics were estimated based on the proportion of the census tract area falling within or outside of the sea level rise.

انتہائی بارش

Source: Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), NYC Stormwater Flood Map—Moderate Flood with Current Sea Levels, 2022. American Community Survey, 2017-2021 5 Year Estimates.

Methodology notes: Population and demographics of residents within the stormwater flood zones were calculated by intersecting the stormwater flood zones with census tracts. Populations and demographics were estimated based on the proportion of the census tract area falling within or outside of the stormwater flood zones.

Source: Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), NYC Stormwater Flood Map—Extreme Flood with 2080 Sea Level Rise, 2022. American Community Survey, 2017-2021 5 Year Estimates.

Methodology notes: Population and demographics of residents within the stormwater flood zones were calculated by intersecting the stormwater flood zones with census tracts. Populations and demographics were estimated based on the proportion of the census tract area falling within or outside of the stormwater flood zones.

Technical Supplement: Potential Improvements to the NYS Disadvantaged Communities Criteria

In 2019, New York State ratified the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, which set forth ambitious climate-focused goals, including GHG reduction requirements, as well as the need to identify the disadvantaged communities that bear the brunt of negative public health effects, existing and historical environmental pollution, and risk of future climate change impacts. As a result of this legislation, the State convened the Climate Justice Working Group, and along with subject matter experts, created and published a methodology for identifying disadvantaged communities (DACs).

The DAC identification methodology considers 45 indicators which describe various socio-demographic and environmental conditions across New York State’s census tracts. These indicators were selected from a larger body of available data comprised of over 100 variables based on data availability, fidelity, and relevance to describing climate justice at the census tract level.

The distillation of over 100 variables to 45 underscores some of the difficulties in capturing how environmental justice is experienced using quantitative data available at the state level. The indicators can only describe phenomena insofar as they are measured, and only at the intervals and scales at which data is collected and released. Facets of environmental justice that are not uniformly measured at the state level are not included in the DAC criteria. There are always differences between lived experience and the conditions that can be recorded through spatial data; datasets do not reflect real time changes nor do they generally capture the nuance and compounding conditions known by communities who have experienced environmental injustices.

Responsive to some of these inherent limitations, the DAC criteria methodology is designed to be updated over time: the State has mandated that the criteria shall be reviewed at least annually in order to improve the methodology where possible. The following analysis of the current criteria aims to contribute to this ongoing refinement and discourse.

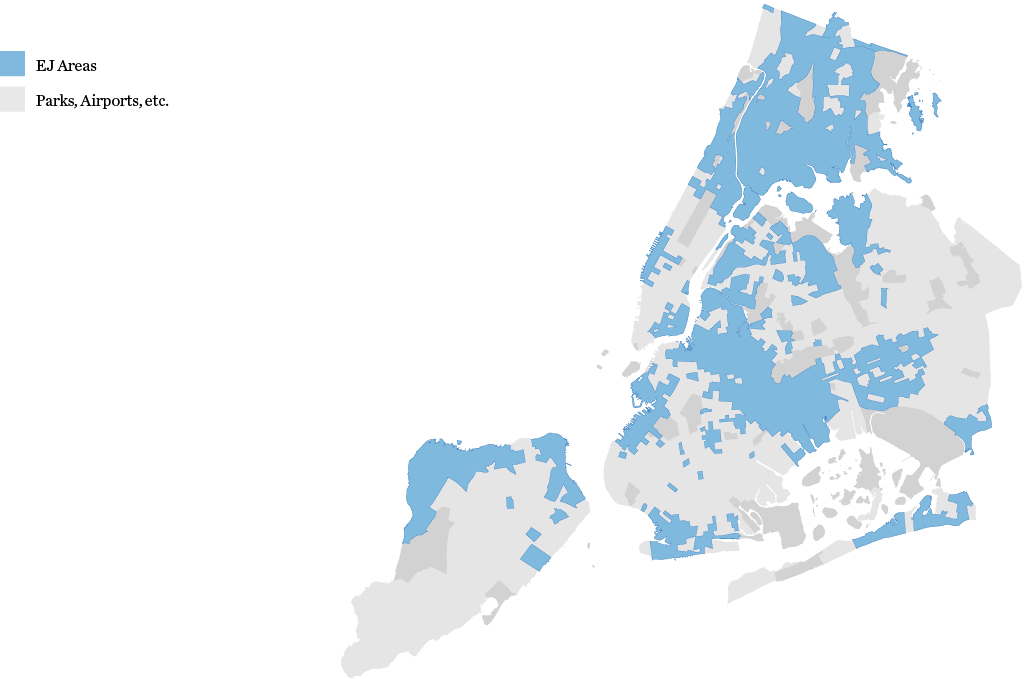

Dacs in New York City

The Climate Justice Working Group determined a target of 35 percent of census tracts in New York State to be designated as DACs. Of the 4,918 census tracts in New York State, 1,736 (35.3 percent) are designated as DACs. Of these, 958 are in New York City, which represent 44 percent of the NYC census tracts and 55 percent of all DACs statewide.

An additional 29 census tracts in New York City are within one percentage point of the threshold used to determine which census tracts are designated as DACs, illustrating that small changes to the selection criteria can have notable impacts on DAC designation. This is significant as DAC designation will determine in part where state spending through the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act is directed, with a target of 35 percent of this funding going towards DAC areas.

DAC Criteria Percentile Rank of Tracts

DAC Designated Census Tracts

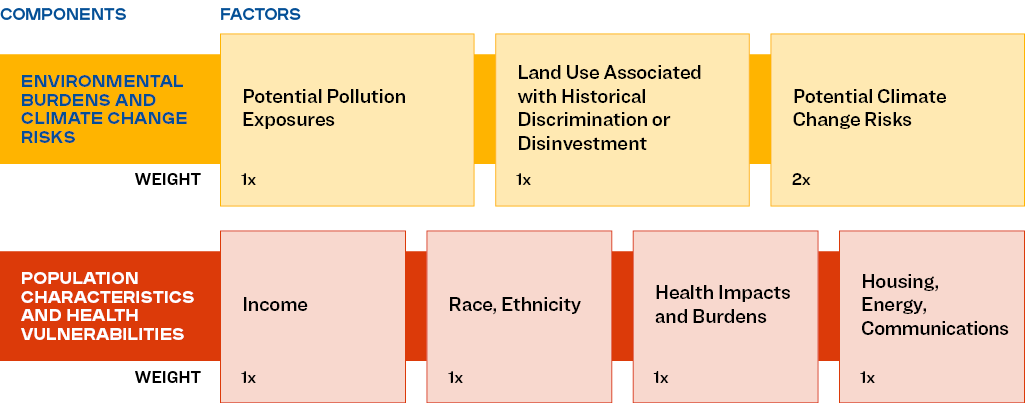

Overview of the Current Methodology

The DAC designation methodology was developed by identifying over 100 potential input datasets and ultimately choosing 45 indicators which were deemed of the appropriate spatial and temporal scale; were based on observations and not proxy or modeled results where possible; and that were available across all of New York State.

Individual indicators were grouped thematically and combined into seven factors. Weighted averages are taken within each factor to provide two component scores which are then summed to inform the final combined score.

Identification Factors and Components Used for the New York State DAC Criteria Methodology

This methodology strives to identify areas that exhibit high scores across both components (Environmental Burdens and Climate Change Risks as well as Population Characteristics and Health Vulnerabilities). However, as a result, there are certain areas in New York State that are not classified as DACs because they score highly in one of the individual components but not both. The following map below shows the geography of these component score disparities across the city in relation to areas that meet the DAC inclusion threshold.

This map displays the difference between Environmental Burdens and Climate Change Risk Score and Population Characteristics and Health Vulnerabilities Score. Deeper blue values denote areas with much higher environmental burden scores than population characteristics scores, and deeper red areas highlight the opposite condition.

This ultimately results in certain tracts with very high scores in one or the other category being excluded from DAC designation. As a result, certain areas that are deserving of attention, either from an environmental burden or public health perspective, do not meet the criteria for inclusion in the DAC. Of particular concern for this report are minority and low-income communities that may have experienced historical disinvestment and detrimental land uses and may experience environmental risks and burdens that are not captured by the current indicators in the criteria, but currently have low scores for Environmental Burdens and Climate Change Risk. Most census tracts in Southeast Queens, for example, are not designated DACs because they do not have a high score in the Environmental Burdens and Climate Change Risks component despite having a high score in the Population and Health Vulnerabilities component.

Comparison between Environmental Burdens and Climate Change Risk Score Percentile and Population Characteristics and Health Vulnerabilities Score Percentile for each tract in New York City. DAC-designated tracts with vulnerability scores of 0 are census tracts with fewer than 500 residents or 300 households which according to the DAC methodology are scored based solely on their burden scores.

Potential Improvements to the State Dac Criteria Methodology

Modifying the Dac Ranking System

A fundamental element of the DAC methodology is that it provides an understanding of burden relative to the rest of the state. A key step in determining this relative burden is to adjust for the extreme indicator and factor scores observed in New York City relative to the rest of the state. This adjustment is made using a multi-step ranking system that ensures that tracts from across New York State are included in the ultimate classification. However, it has the effect of excluding New York City census tracts that would otherwise be classified DACs.

As currently constructed, tracts in New York City are eligible to be included as DACs if they are within the top 29.8 percent of tracts statewide, or in the top 29.8 percent of tracts in the rest of New York State (excluding NYC). The secondary filter (adding tracts if they are within the top of the rest of New York State ranking) is designed to add to the share of DACs that are outside of New York City. In total, 44 percent of NYC tracts and 29 percent are tracts in the rest of the state are DACs based on the current methodology. If only the statewide ranking were used, 55 percent of NYC tracts would be included, and 20 percent of tracts in the rest of the state would be included.

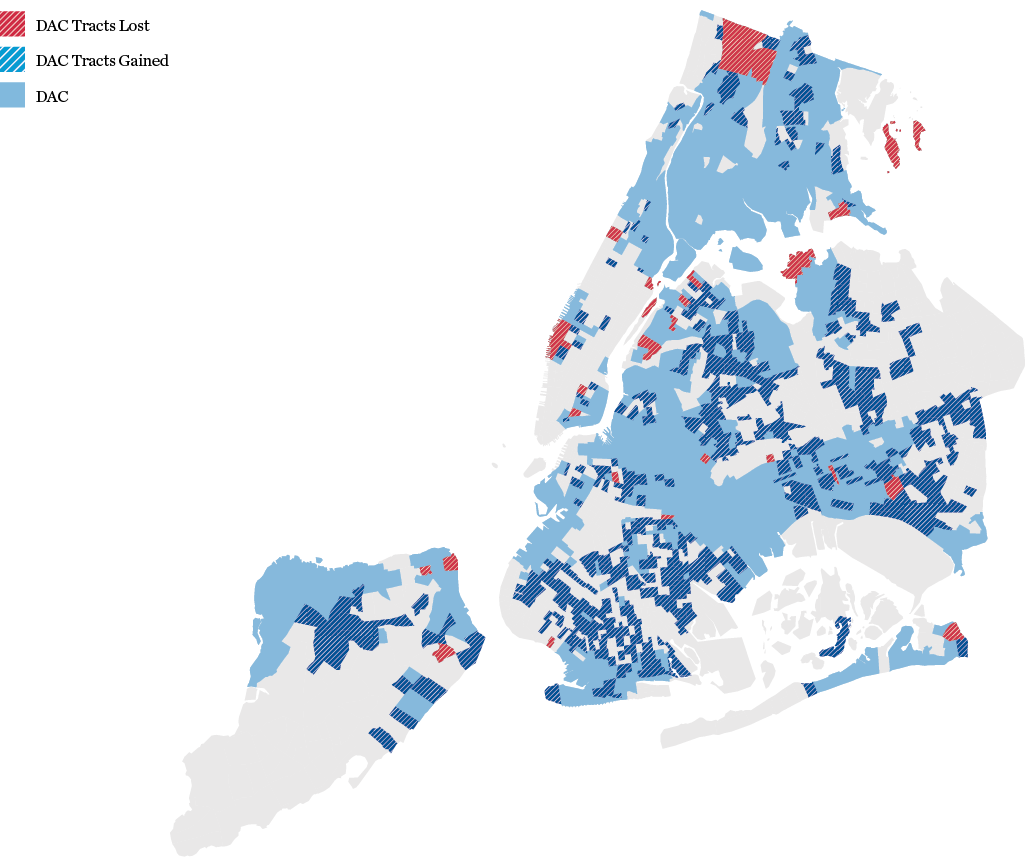

Changes to DAC Census Tracts that Would Result from Using a Statewide Ranking Method Only

This map displays changes to DAC census tracts that would result from using a statewide ranking method only, instead of also separately considering rankings among tracts outside of NYC.

Modifying the Dac Indicators

Several indicators were identified that should be considered for inclusion or exclusion in future revisions to the DAC criteria.

Pluvial Flooding

The current DAC indicator related to inland flooding excludes pluvial flooding which occurs when extreme rainfall creates a flood independent of an overflowing water body. This is a major issue for New York City and other urban communities throughout the state, where this type of flooding is more prevalent due to a greater proportion of impervious surfaces. During Hurricane Ida, the confluence of stormwater flooding and housing insecurity caused devastating loss of life in below-grade apartments in NYC. The data currently employed in the DAC methodology to calculate this indicator were generated through projecting future flooding for streams in the US under a future climate change scenario and quantifying increased risk within current FEMA FIRMs . This dataset provides an important baseline understanding of inland flood risk from overflowing water bodies (fluvial flooding); however, the NYC Stormwater Flood Map – Extreme Flood with 2080 Sea Level Rise dataset, provided by the City of New York, provides a more complete understanding of inland flooding, incorporating pluvial flooding. Statewide analysis of stormwater flooding should be conducted so that this significant measure of climate change risk can be included for communities statewide. Adding this indicator to the current methodology would add 112 DAC census tracts in NYC and would cause 114 additional DAC designations to be redistributed to other tracts within NYC. More information on this updated measure can be found in the DAC Additional Indicator Methods call-out box.

Noise Pollution

Noise pollution was considered as an indicator in the drafting of the DAC criteria, however no dataset existed at that time. In November 2022, the US Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS) published the National Transportation Noise map, which represents the intensity of transportation-related noise pollution based on 24-hour equivalent sound levels for aviation, road, and rail-based transportation. While BTS outlines limitations of this dataset, it provides insight into the geography of noise pollution across New York State and is presented for consideration for inclusion in the DAC criteria in the future. Adding this indicator to the current methodology would add 129 DAC census tracts in NYC and would cause 81 additional DAC designations to be redistributed to other tracts within NYC. More information on this updated measure can be found in the DAC Additional Indicator Methods call-out box.

Proximity to Wastewater Discharge

This measure scores census tracts based on how close they are to polluted streams as measured by the EPA. The score is weighted by toxicity of the pollutants measured and includes all census tracts within 500 meters of streams for which there are data. This indicator identifies tracts along the East River and Long Island Sound in Manhattan, Queens, the Bronx, and Brooklyn, as well as tracts along Arthur Kill in Staten Island as tracts proximate to wastewater discharge. The current method used for this indicator allocates pronounced values in the above-mentioned areas, and no data values for most of Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island. In addition to the limited geography where this criterion is applied, proximity to wastewater discharge alone does not correspond with exposure to pollution for several reasons. The proximity-based measure does not distinguish between treated wastewater, which must meet effluent limits designed to ensure that water quality standards in the receiving water body are not exceeded, and untreated combined sewer overflow. Moreover, proximity does not necessarily lead to exposure. Independent of water quality, many of the waterbodies in and around the city are not suitable for swimming because of boat traffic or current, and the proximity metric does not take elevation or topography into account and includes large portions of upland neighborhoods unlikely to be impacted by this potential pollutant. It is highlighted for consideration for exclusion from the DAC criteria in the future. Removing this indicator from the current methodology would add 115 New York City census tracts as DACs and would cause 90 additional DAC designations to be redistributed to other tracts within NYC.

Housing Vacancy Rates

The rationale provided in the DAC criteria methodology states that this measure was included to measure disinvestment from a community; however, due to market dynamics and other factors, the highest rates of housing vacancy in New York City occur among high-cost and luxury housing. While this trend may vary for other portions of the state, including this variable for New York City does not capture the intended trends and it is highlighted for consideration for exclusion from the DAC criteria in the future; removing this variable from the overall criteria calculation adds an additional 116 DAC tracts to New York City, and redistributes an additional 89 tracts within NYC.

Combining the Potential Modifications to the Dac Criteria Methodology

To illustrate the potential impacts of the combined adjustments to the DAC criteria outlined above a composite revision to the criteria was computed. This potential update to the DAC methodology used a statewide ranking only, added indicators for stormwater and noise, and removed indicators for wastewater and housing vacancy. The combined impact of these adjustments to the criteria would add 485 DAC census tracts in NYC and redistribute 15 tracts within the city. Using this method, 65 percent of census tracts in NYC would be DACs, compared with 12 percent of census tracts outside of NYC.

Map displaying changes to DAC census tracts that would result from using revised methodology that uses a statewide ranking, adds indicators for stormwater flooding and noise and removes current indicators for wastewater discharge and housing vacancy.

Taken together these convey considerations for the Climate Justice Working Group and NYS Department of Environmental Conservation in the next iteration of the DAC criteria methodology. This case-making analysis illustrates how the methods used impact which communities are considered DACs and which are not. The concerns outlined here should be considered as the Climate Justice Working Group and NYS Department of Environmental Conservation continue to refine the DAC criteria to best describe communities facing environmental and climate burdens in New York State.

Changes to DAC Status with Combined Updates to Method

Dac Additional Indicator Methodology

Pluvial Flooding

For the pluvial flooding indicator, this analysis used data from the NY Stormwater Flood Map – Extreme Flood with 2080 Sea Level Rise. This dataset was chosen because it is the publicly available stormwater flooding dataset that is most consistent with the flood risk and climate change projections used by the inland flooding indicator utilized in the original DAC Criteria in that it:

- Represents flooding from a 100-year flood event (consistent with existing DAC inland flooding indicator)

- Uses 2080 sea level rise anticipating 4.8 feet of sea level rise (existing DAC inland flooding indicator used 2100 projected sea level rise, but a lower estimate of 3 feet of sea level rise)

- This dataset contains data for three levels of stormwater flooding severity:

- Between 4 inches and 1 foot

- Greater than 1 foot

- Future high tides 2080

For each census tract, the percentage of each tract covered by flood zones of each severity was calculated. To account for these three levels of severity when combining the scores, they were then weighted accordingly: (1-3x the percentage calculated). These weighted percentages were then added together, and a percentile ranking was conducted to determine the final percentile ranking for each tract.

To develop a revised DAC score given the lack of equivalent stormwater flooding data for areas outside of NYC, the inland flooding indicator was used for the rest of the state and the new stormwater indicator was used for NYC. Combined scores were calculated based on these different indicators for NYC vs the rest of the state.

Noise

For the noise indicator, this analysis used data from the DOT National Transportation Noise Map for aviation, road, and rail noise. This is a raster dataset which records the distribution for all noise above 45dB(A) taking into account attenuation rate:

“Attenuation Rate: In this model, noise level attenuation is considered to be due only to ground effects and free-field divergence. Shielding is not considered (i.e. attenuation due to barriers and terrain are not considered). For this reason, noise levels may be over-predicted in areas near highway barriers or natural shielding features such as berms, hills, etc.”

For each census tract, the percentage of each tract’s area with noise over 45dB(A) was calculated. The threshold of 45dB(A) is the minimum value available in this dataset and was chosen because it is the threshold defined by the Word Health Organization as a maximum dB level for healthy noise exposure. A percentile ranking was conducted to determine the relative presence of noise pollution within census tracts in New York State.

Program/policy Spotlight Methodology

Overview

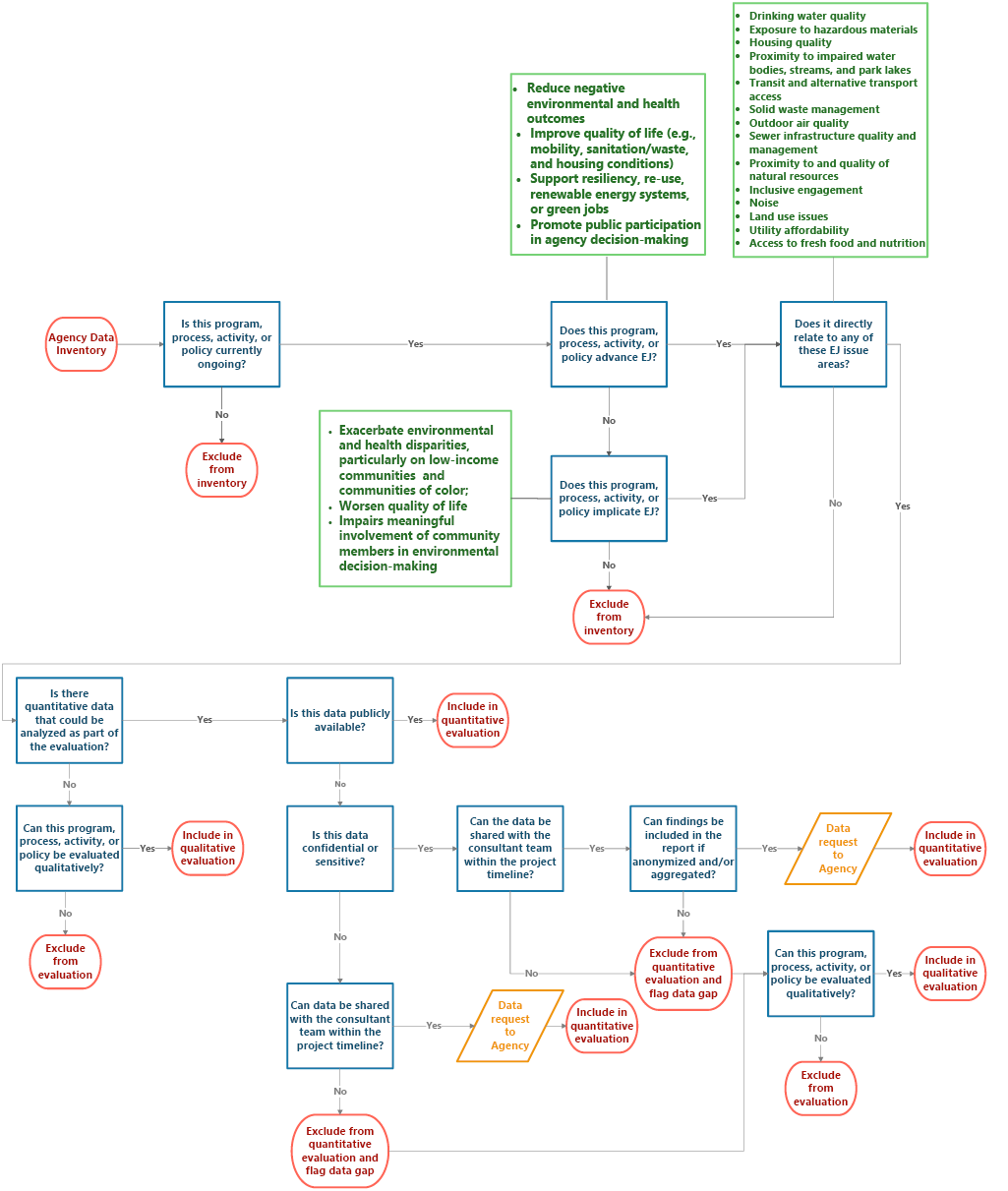

A program evaluation is a systematic method for collecting, analyzing, and using data to answer questions about the efficacy and efficiency of programs, and contribute to continuous improvement. They are typically used to examine whether particular a program is producing its intended effect. For the EJNYC Report, the program evaluation approach differed from a typical program evaluation as the mandate was to assess whether multiple City programs and processes advanced or exacerbated environmental justice concerns, regardless of whether they were intended to do so or not. Additionally, the scope of this analysis was limited due to time limitations and data availability. For this reason, the outputs of these evaluations are called “Program/Policy Spotlights” in this Report.

- This program/process evaluation was developed based on content requirements outlined in the EJ Report Scope. The EJ Report Scope is a formalized document chronicling input from a public scoping process that included thousands of comments from New Yorkers and determined the direction of the EJNYC Report. Per the Scope, the aim of the program/process evaluation is to examine existing city programs and processes that either advance environmental justice goals or exacerbate environmental justice concerns and examine processes may be used by the public to participate in City agency decision-making.

Key questions this evaluation set out to answer include:

- Which EJ concerns are impacted by the given program/process?

- Which groups and neighborhoods are most impacted? How closely does the program impact meet the scale and severity of the problem it is meant to address?

- How well-funded is the program and what is the distribution of investment throughout the city? Are funds and investments made equitably and proportional to the burden faced by different communities?

- Does the program pursue equity and environmental justice explicitly?

- What is the agency’s outreach process for sourcing public comments? What barriers impact public participation in environmental decision-making?

- How well are the outcomes of this program being monitored?

To conduct this assessment, a mix of quantitative and qualitative inputs were analyzed, including population data, program budgets, case studies, program monitoring reports, stakeholder conversations, and literature reviews of existing research. Due to data constraints, the depth of analysis varies and not every program, policy, and process could be evaluated against these questions.

Data Collection

Data collection for the program/process evaluation was a multi-phase process beginning with the curation of a comprehensive list of over 100 City programs and processes related to environmental justice concerns. This preliminary list was informed by a survey shared by MOCEJ to EJ IWG member agencies and inputs from the EJAB on relevant initiatives, policies, and actions which either advance or implicate environmental justice and/or relate to public engagement in environmental decision-making.

Following the creation of the preliminary list, a screening framework was used to screen each entry on the list to ensure only the most relevant programs/processes—and those that could be readily evaluated qualitatively or quantitatively—were moved forward to analysis. This screening framework was developed through an iterative process with feedback from MOCEJ, EJ IWG, and EJAB. The framework, shown below, is made up of two main parts – the first raising topical questions on the program’s suitability for the EJ evaluation, and the second addressing data quality and availability.

Program/Process Screening Process

The EJ Report Scope required that each environmental concern listed in the Scope was represented at least once in the program/process evaluation. To satisfy this requirement, a second round of solicitation for relevant initiatives was conducted by MOCEJ. The logic model was applied to the additional initiatives. Ultimately, 33 programs/processes that either mitigate or exacerbate EJ concerns and 10 processes that facilitate public participation in environmental decision-making moved forward to the data sourcing phase.

Publicly available City data including geospatial layers, spreadsheets, press releases and program monitoring reports were obtained from NYC OpenData and agency websites. Additional research was conducted to source external data from research papers, articles, and books. In some instances where data gaps existed, non-published City data sources were identified through conversations between MOCEJ, EJ IWG member agencies, and the consultant team. However, much of these data could not be made available within the project timeline. This data gap led to a truncated selection of programs for evaluation and also limited the scope of analysis for some evaluated programs.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted as appropriate for each program/process to answer the guiding questions outlined above. For the spatial and demographic analyses, 2010 census tracts were used alongside 2021 ACS 5-year Estimates unless otherwise stated. 2010 census tracts were used to maintain consistency with the New York State Disadvantaged Communities criteria which have been used throughout this evaluation as the definition of “EJ Areas.”

Get Stuff Built: Building and Land Use Approval Streamlining Taskforce

(BLAST) Plan

Qualitative analysis of the 2022 Get Stuff Built Plan was developed following literature review of the plan itself, the CEQR Technical Manual, ULURP rules, and the DOB permitting procedure alongside existing research around land use and environmental justice in New York City. The proposed actions were examined for their potential impact on EJ considerations, such as environmental review and infrastructure siting especially in EJ communities.

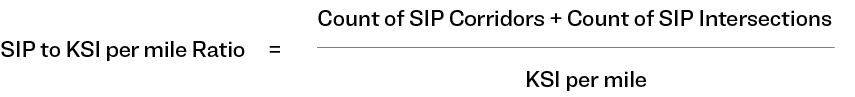

Vision Zero

Qualitative and quantitative data were used for this program spotlight. For the qualitative analysis, program reports were reviewed. Quantitative data used includes 2017-2022 Serious Injuries and Fatalities (KSI) data from NYPD and Vision Zero Street Improvement Projects data on NYC OpenData. A spatial join using the “contain” predicate was computed in GIS software to combine census tracts and crash data. The result was used to determine trends in the occurrence of KSI crashes in EJ Areas and non-EJ Areas.

In addition to KSI trends in EJ Areas versus non-EJ Areas, the KSI per mile metric was computed to determine locations with the most and least prevalent traffic safety concerns. This KSI crash density was calculated by dividing the number of KSI in each NTA by the total length of roadway within the tract boundary. The NTAs were then ranked by percentile with 0-10 having the lowest KSIs per mile and 90-100 having the highest.

A spatial join of census tracts and Street Improvement Projects (SIPs) at intersections and along street corridors contained in the tracts boundaries was computed to identify where investments have been directed. To compare the incidence of serious crashes and fatalities to program interventions, the ratio of SIPs to KSI per mile was computed follows:

Data gaps: this analysis only considers 2017-2022 and not the full program lifetime (beginning in 2013) because of data availability issues. An alternative NYSDOT dataset with 2013-2020 KSI crash data was explored but ultimately rejected in favor of the more recent NYPD 2017-2022 data.

Nyc Community Air Survey

This program spotlight was developed through a review of program reports published by DOHMH alongside air quality studies conducted by community-based organizations.

Nyc Clean Trucks Program

Qualitative and quantitative data from program reports, eligibility guidelines and citywide truck traffic studies were used to conduct this analysis. The program’s impact towards reducing truck emissions was measured by the number of replaced trucks divided by the number of trucks making daily crossings in and out of the city. This estimate assumed that each truck enters and leaves the city once daily, thus the total number of intercity trucks is equal to half the number of daily crossings in and out of the city.

Analysis of program eligible areas was performed by creating a 0.5-mile buffer around participating IBZs and selecting census tracts that fell at least partially within the buffer areas.

Hunts Point was excluded from the analysis of funding distribution in eligible IBZs because the neighborhood had an eight-year head start and an outsized level of funding compared to the other IBZs. Funding to non-domiciled trucks was also excluded from the analysis as there was no data on their locations, eliminating the possibility of any spatial analysis.

Environmental Remediation

Inputs for this evaluation include program reports, site enrollment data from program inception through 2022, and existing research on environmental remediation in New York City. Spatial joins of census tracts and VCP sites, and community districts and VCP sites were computed to examine the incidence of clean-up projects across the city and in EJ Areas compared to non-EJ Areas.

Demographic analysis was conducted by comparing 2010 ACS 5-year estimates to 2021 ACS 5-year estimates results for census tracts with VCP sites.

Data gaps: Confirmed knowledge of contamination in NYC is largely limited to sites where testing has been conducted as part of environmental review for land use approvals and special permits. As such, environmental contamination in neighborhoods with low development demand is likely to go undetected and untreated.

Alternative Enforcement Program

Qualitative evaluation for this program was developed using program reports, housing code enforcement rules, and the NYC Housing and Vacancy Survey.

Nycha Customer Contact

This program assessment mostly relies on qualitative inputs from the NYCHA website, press releases and quarterly reports from HUD’s independent monitor. Spatial analysis of distance between NYCHA developments and customer contact centers was conducted in GIS software.

Data gaps: This evaluation would have benefitted from access to NYCHA complaint, response, and resolution logs to assess the success of the Customer Contact program as well as other stakeholder criticisms around poor maintenance operations.

Cso Long-term Control Plans

This spotlight focuses on the distribution of stormwater infrastructure and investment in EJ and non-EJ Areas. Program funding amounts for completed projects in each sewershed were sourced from 2022 Q4 reports.

Spatial intersection was computed between LTCP sewersheds and census tracts to determine program impacts in EJ Areas vs. non-EJ Areas.

Lead Service Line Replacement

Qualitative assessment of DEP’s Lead Service Line Replacement pilot program program was developed using reports, insights obtained through conversations with DEP staff, and Drinking Water State Revolving Fund program documents.

Data gaps: The material composition of service lines in New York City is not fully known, with 16 percent of service lines potentially containing lead and 26 percent having unknown composition. As such, the scope of the challenge before DEP’s Lead Service Line Replacement program is not fully represented.

Cool Neighborhoods

Qualitative assessment for this program was developed using published reports from the City. Spatial analysis of Hyperlocal Temperature Monitoring data involved a spatial join of census tracts and monitor locations. ACS data for each census tract with monitors were aggregated to give demographic characteristics of benefitting neighborhoods.

Qualitative Research Methodology

New York City is home to an expansive network of competent, energetic and dedicated community leaders improving their neighborhoods and organizing to address the interconnected quality of life issues that comprise the environmental justice movement across the city. This leadership is found from the hyper-local, neighborhood scale to citywide and regional scales, and is present in both formalized leadership roles (such as at community-based and not-for-profit organizations, civic associations, and community boards), as well as informal roles (like those on the block in our neighborhoods, in school classrooms, and in local volunteers). They range in age from high school students to retired adults and are as diverse as the multitude of identities of the city itself. Through their persistent labors, these leaders and their communities have crafted visions, plans and achieved considerable successes and improvements in environmental justice and quality of life issues.

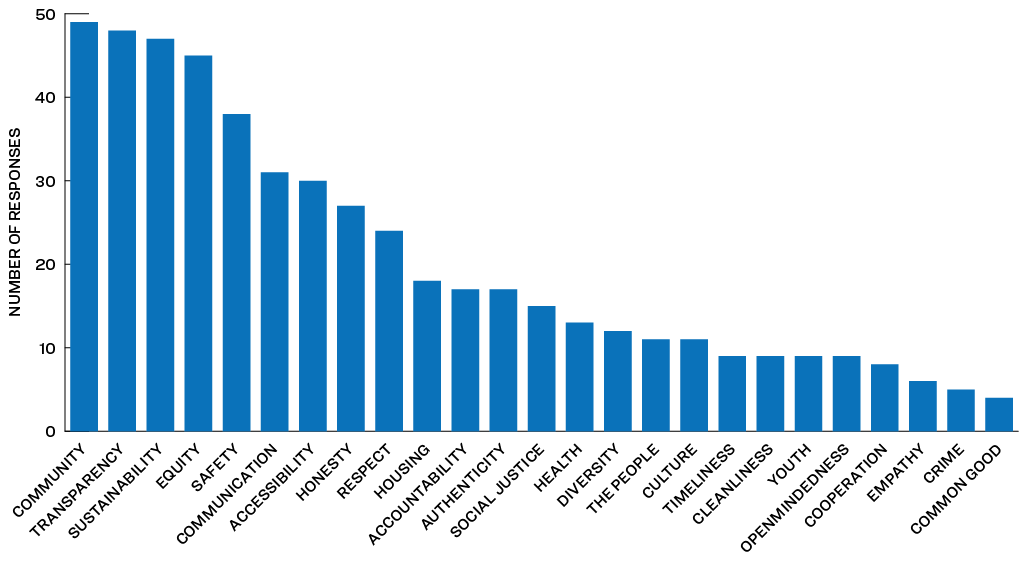

Through interviews and focus groups, the EJNYC Qualitative Research Team spoke with 42 New Yorkers living or working in environmental justice communities from across the five boroughs about the challenges they face with regards to the effects of environmental injustices, how they are managing these issues, and what their experiences have been in engaging with the City’s related programs and decision-making processes.

Qualitative Approach

The purpose of the qualitative assessment was to elevate the lived experiences of historically overburdened and underinvested communities in assessing the City’s historic and current contributions to environmental justice, with a focus on relevant City policies, programs, decision-making processes, public engagement practices, and access to data and information. The assessment was two-pronged in its approach, including both interviews with NYC environmental justice organizational leaders, as well as focus group sessions with everyday residents and community members on the ground in environmental justice communities, altogether seeking a limited, yet representative sample of both community members and formal leaders. All participants were compensated for their time and contributions.

Focus Groups with EJ Community Residents

The team held five focus groups virtually from late-August to early-October, reaching 22 New Yorkers across each of the five boroughs and throughout various neighborhoods identified as environmental justice communities. Participants represented a range of racial and ethnic identities, ages and gender identities, with 41 percent of participants identifying as Black or African American (followed by 23 percent identify as Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Filipina) and 43 percent of participants identifying as of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin. The majority of participants (65 percent) identify as female, and nearly half of participants (47 percent) are between the ages of 25-44. One quarter (25 percent) of participants are NYCHA residents.

In the focus group sessions, participants were engaged with questions and conversation prompts ranging from “Share an experience where you were affected by an environmental issue. How did it affect you and how did you manage or resolve it?” to “What decision-making processes have you participated in (or not)? How was your experience? How should these processes change to lead to better outcomes for you and your community?”.

Interviews with Environmental Justice Organizational Leaders

The team also held sixteen interviews with environmental justice leaders, including two dozen executive directors of community-based and/or advocacy organizations, their staff, researchers who focus on NYC environmental justice and were recommended by community leaders, and NYCHA resident representatives. The Interviewees represented (or worked with) organizations that are based in communities across the five boroughs:

- 31 percent (5) in Brooklyn

- 13 percent (2) in the Bronx

- 19 percent (3) in Queens

- 13 percent (2) in Staten Island

- 25 percent (4) citywide, including two NYCHA representatives

Textual data from both the focus groups and interviews were reviewed, categorized, and interpreted through an iterative and inductive qualitative coding methodology, allowing insights and themes to emerge from the data and thus the voices of participants, rather than tested against a hypothesis. This assessment also included feedback and additional input from the NYC Environmental Justice Advisory Board, which includes representatives from across the city, including Manhattan-based organizations.

Supplement: City Programs and Initiatives

The following list is representative of City programs designed to address EJ issues. The list is not exhaustive but may serve as resource for individuals and organizations seeking programs and initiatives that address various EJ issues. The resources are organized by section from The State of Environmental Justice chapter and sorted chronologically, where applicable.

Access to Resources

Equitable Development Data Explorer (DCP & HPD)

Developed out of advocacy by the Racial Impact Study Coalition (RISC) and Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, the explorer uses data on housing and demographics to indicate the level of displacement risk in different neighborhoods.

Local Law 78 of 2021 (City Council)

LL 78 requires the preparation of Racial Equity Reports for certain land use changes, including a community profile from the Equitable Development Data Explorer, a narrative statement on the how the project affirms the City’s fair housing strategy, and the project’s anticipated housing units and jobs.

Racial Justice Commission (Charter Revision Commission)

In 2021, the City convened a Racial Justice Commission to examine barriers faced by people of color, propose revisions to the City Charter, and draft ballot proposals that forward racial equity. All three of the Commission’s final ballot measures, including the creation of Office of Racial Equity and a citywide Racial Equity Plan, were approved by a referendum of voters in November 2022.

Better Buses Action Plan (DOT & MTA)

DOT and MTA use equity metrics for prioritizing areas that can most benefit from speed and reliability improvements, including population of car-free households and low-income households. Many completed routes are in EJ communities, including the Bx12 SBS in Upper Manhattan and the Northern Bronx, the B44 SBS and B46 SBS in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, and Flatbush in Brooklyn, and the Q44 SBS connecting the Northern Bronx with the Flushing and Jamaica neighborhoods in Queens.

OMNY Fare-Capping Program (MTA)

The fare capping program allows transit riders who take more than 12 trips per week to ride free for the remainder of the week. This flexibility allows low-income riders to achieve savings over single ride fares without having to prepurchase an unlimited pass.

Metro-North Railroad Expansion (MTA)

Access to rapid transit plays a critical role in expanding access to economic opportunities by reducing commute times. The four new stations in Hunts Point, Parkchester/Van Nest, Morris Park, and Co-Op City will bring rapid transit service within a mile of 500,000 residents. The project, to be completed in 2027, will reduce travel time from the Bronx to Manhattan by as much as 50 minutes.

NYC Ferry Forward Plan (NYCEDC)

Introduced in Summer 2022, the plan aims to make the ferry system more equitable, accessible, and financially sustainable., including objectives to broaden outreach to NYCHA developments near the ferry landings and expand the discount program to offer $1.35 one-way tickets for seniors, people with disabilities, and other riders who participate in the Fair Fares NYC program.

Zoning for Accessibility (DCP, MTA, and MOPD)

To create a more accessible transit network, ZFA is a citywide zoning amendment that incentivizes private developers to build transit accessibility improvements in exchange for a density bonus.

Off-Peak Frequency Enhancements (MTA)

MTA introduced a plan to increase off-peak service by 2024, focusing enhancements on areas where subway ridership has recovered the highest from its pre-pandemic baseline. These enhancements can benefit workers in the outer boroughs with nontraditional work schedules that rely on off-peak transit service.

Free Fare Pilots (MTA)

Starting in September 2023, MTA will begin free fare pilots on five bus routes, one in each borough. The pilots will last 6-12 months on the following routes: Bx18 A/B, B60, M116, Q4 LCL/LTD, and S46/96. Routes were chosen based on a variety of factors, including ridership, equity for low-income and economically disadvantaged communities, and access to employment and commercial activity.

SAFEMicromobility (NYCHA)

Safe Access for Electric Micromobility (SAFEMicromobility) is NYCHA’s plan to provide safe and secure outdoor charging stations for electric micromobility devices like e-bikes and e-scooters to its residents. NYCHA has partnered with Con Edison for a demonstration project at four developments, and in June 2023, was awarded a $25 million federal grant through the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) program for the installation of 173 outdoor charging stations at 53 developments. This program promotes safety and equitable access to e-micromobility charging to residents in environmental justice communities.

Priority Investment Areas (DOT)

Through the NYC Streets Plan, DOT established Priority Investment Areas to act as a tool to focus future investment to where it can have the greatest impact. Identification of PIAs is based on the NTA’s percentage of non-white residents and low-income residents, job and population density, and previous DOT investment.

Fleet Safety Initiatives (DCAS)

DCAS has implemented a comprehensive set of road safety measures to bolster the overall safety of the City’s vehicle fleet. This includes the installation of surround cameras and backup sensors, the integration of intelligent speed assistance (ISA) to enforce maximum speed restrictions, and the establishment of the Fleet Office of Real-Time Tracking (FORT). FORT efficiently utilizes telematics to monitor the usage patterns of the City’s fleet. As a result of these proactive measures, along with other road safety initiatives, there has been a 23 percent decrease in preventable collisions involving City-owned vehicles (excluding NYPD) since 2019.

Community Parks Initiative (NYC Parks)

This initiative is designed to use future programming and park and playground rehabilitation efforts to address the historic disparities in park investment by identifying priority zones based on population growth, population density, and poverty rates. So far, the program has invested $285 million in 65 parks across the city, including in EJ communities in the South Bronx, Upper Manhattan, Central Brooklyn, and along the North Shore of Staten Island.

NYC Waterfront Public Access Study (DCP)

DCP conducted the Waterfront Public Access Study to better understand New Yorkers’ access to open space along NYC’s 520 miles of waterfront and to support the NYC Comprehensive Waterfront Plan released in December 2021. In addition to informing the Comprehensive Waterfront Plan’s Waterfront Public Access goals, the study findings will be used by DCP and other City agencies to support forthcoming waterfront zoning studies to expand waterfront public access.

Food Retail Expansion to Support Health (FRESH) (NYCEDC & DCP)

To support the expansion of fresh food sources, the FRESH program provides zoning and tax incentives to supermarket operators and developers. To date, 30 projects, predominantly in Upper Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx, have been approved, securing 2,000 jobs for their local communities. In 2021, DCP amended the program to limit oversaturation and expand the zoning boundary to more neighborhoods in the outer boroughs.

Mayor’s Office of Urban Agriculture (MOUA)

In the absence of grocery stores and supermarkets in many EJ communities, residents have launched urban farms and community gardens. Through collaboration with other City agencies, MOUA will promote the growth of urban agriculture through research, policy development, advocacy, and community outreach.

Health Bucks (DOHMH)

Health Bucks are $2 coupons that can be used to purchase fresh fruit and vegetables at New York City farmers markets. For every $2 spent at a farmers market using an EDT card, SNAP recipients receive $2 in Health Bucks, up to $10 a day.

Exposure to Polluted Air

Solar (DCAS, MOCEJ, NYCEDC, and NYCHA)

In One City: Built to Last the City has committed to achieve 100MW of solar energy generation on City-owned property by 2025 through multiple strategies which include large scale non-rooftop solar, and repair and replacement of high-priority rooftops. One City: Built to Last committed the City to assessing City building rooftops for solar readiness. The City is also working to support the installation of solar on privately owned buildings, and facilitate community solar projects that can benefit New Yorkers who do not own buildings. In addition to the City’s 100MW goal, NYCHA has committed to installing 30MW of rooftop solar by 2026. As of 2023, NYCHA has 19.7MW of solar in its pipeline via its ACCESSolar program and PACT developers: 6.7MW have been installed; 3MW are under construction; and a solicitation for another 10MW was released in April.

Offshore Wind NYC (NYCEDC)

NYC committed to $191 million in offshore wind investments over the next 15 years. Investments will focus on offshore wind sites and infrastructure, business and workforce development, and research and innovation to attract offshore wind development to the city.

Offshore Wind NYC Waterfront Pathways Program (NYCEDC)

Offshore wind development will bring good-paying clean energy jobs and contracting opportunities for NYC businesses. The Offshore Wind NYC Waterfront Pathways Program supports minority-owned, women-owned, and disadvantaged business enterprises in receiving contracts from NYCEDC to work on offshore wind opportunities.

Citizens Air Complaint Program (NYC DEP)

Allows citizens to participate in the enforcement of the idling laws by reporting an illegally idling vehicle. The Idling Complaint System enables citizens to file and track idling complaints and receive an award if the summons is upheld.

Clean Air (Port Authority of NY NJ)

The Port Authority of NY NJ has multiple environmental initiatives to address the air pollution impacts of ports and airports, including electrifying buses and other vehicles, adding electric vehicle charging stations for Port Authority customers, electrifying ground support equipment at airports, supporting the purchase of new, cleaner cargo handling equipment, incentivizing the use of clean maritime vessels, and supporting the use of sustainable aviation fuel.

نیو یارک کو بجلی فراہم کرنا (NYC DOT)

Electrifying New York is an electric vehicle vision plan that lays out goals to support the adoption of electric vehicles over the next decade. The plan calls for expansion of fast charging networks, equipping parking lots and garages with chargers, advocating for additional funding, working with utilities to make it easier and cheaper to install electric vehicle chargers, engage with stakeholders and increase public awareness about electric vehicles.

NYC Clean Fleet Plan (DCAS and NYCHA)

NYC aims to be the most sustainable fleet in the country through the NYC Clean Fleet Plan, originally issued in 2015 and updated in 2021. NYC is working to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 50 percent by 2025 and will accelerate the transition of all light duty and medium duty on-road fleet vehicles, including law enforcement and emergency response models, and all non-emergency trucks to an all-electric on road fleet by 2035. Emergency and specialized trucks will be converted to electric models no later than 2040. In alignment, NYCHA released its own Clean Fleet Plan to reduce NYCHA’s vehicle-related carbon emissions by 40% by 2028. Additionally, NYCHA has collaborated with DCAS to host solar car-port electric vehicle charging stations at its developments.

Electric Micromobility Action Plan (Mayor’s Office)

The Mayor’s Office convened an Interagency Electric Micromobility Task Force to develop a Micromobility Action Plan to support New Yorkers in transitioning to safe and legal e-micromobility, prevent fires, prevent crashes, support delivery workers, promote sustainability and access, improve emergency response and educate the public about the safe use of electric micromobility.

فریٹ NYC (NYCEDC)

Freight NYC outlines four goals to address the air quality impacts of the city’s freight network. These goals include the creation of thousands of jobs in the freight sector, investing in maritime and rail infrastructure, modernizing and developing new distribution facilities, and building an environmentally sustainable and resilient supply chain.

Hunts Point Produce Market redevelopment (NYCEDC)

In September 2022, Mayor Eric Adams announced that the Hunts Point Produce Market would receive $110 million in federal grant monies to upgrade its facilities. The grant will be used to strengthen critical freight movement and improve the environment, public health, and quality of life for the Hunts Point community. The redevelopment of the Hunts Point Produce Market will eliminate about 1,000 temporary refrigeration units on site that are diesel-powered and idling on site. The new site will have an updated traffic circulation plan that will significantly reduce emissions attributed to onsite congestion and idling. There will also be a projected increase in rail usage, and installation of conduit to support future freight EV charging.

Idling Regulations (NYC Business)

The New York Anti Idling Law updated the New York City Administrative Code to disallow engines of motor vehicles from idling for longer than three minutes. This regulation does not apply to emergency motor vehicles or vehicles whose engine is used to operate loading, unloading, or processing devices.

MTA 2020 – 2024 Capital Plan (MTA)

In its 2020-2024 Capital Plan, the MTA committed to transitioning to a 100 percent zero-emissions fleet, starting with the purchase of 500 new electric buses.

NYC Clean Trucks Program (NYC Business)

The Clean Trucks Program offers rebates between $12,000 and $185,000 to replace older, heavily-polluting diesel trucks with electric, hybrid, or newer vehicles.

Curbside Composting (DSNY)

The Department of Sanitation is rolling out Curbside Composting citywide throughout 2024 following the successful implementation of a curbside composting program in Queens. All New Yorkers will be required to separate leaf and yard waste, food scraps, and food soiled paper for collection at the curb per the Council’s Zero Waste bills.

Drop-Off Composting Sites (DSNY)

Smart Composting Bins are available across the city for food scrap and plant waste drop-off, in addition to community-based drop off sites. New Yorkers need to download the NYC Compost app for iOS or Android in order to use the Smart bins.

Clean Curbs for All (NYCHA)

NYCHA’s Clean Curbs for All pilot is a hoist-collected waste containerization and electric trucks at five developments in South Brooklyn. Clean Curbs for All aims to reduce the pests at NYCHA developments by removing non-containerized trash from sidewalks, while mitigating the cumbersome and dangerous physical lifting and handling by NYCHA caretakers; truck pollution and noise associated with garbage pick-ups; and large open sources of trash, leading to cleaner developments and grounds.

2018 کا مقامی قانون 152 (City Legislation)

In 2018, the Department of Sanitation was required to reduce permitted capacity at private transfer stations in Brooklyn Community District 1 by 50 percent and in Queens Community District 12 and Bronx Community Districts 1 and 2 by 33 percent to comply with the Waste Equity Law. These communities, which are primarily home to EJ communities, saw a majority of the city’s solid waste processed in their neighborhoods, an injustice which the Waste Equity Law addressed.

NYC Compost Project (DSNY)

The Department of Sanitation operates a citywide compost education and outreach program in partnership with botanical gardens and composting nonprofits in all five boroughs to provide workshops and technical assistance for home or community-based composting.

Solid Waste Management Plan (DSNY)

The Department of Sanitation’s Solid Waste Management Plan outlines the agency’s structure and strategies for managing the city’s solid waste through 2026. Efforts are underway to develop the next Plan, which will prepare for 2026 through 2036, and beyond.

کمرشل ویسٹ زونز (DSNY)

Local Law 199 of 2019 required the establishment of Commercial Waste Zones. These 20 zones were created to reduce commercial waste disposal and incentivize recycling, reduce truck traffic, provide fair pricing, strengthen customer service, improve training, safety, and labor standards, invest in clean fleets, and build resiliency in the city’s waste carting system.

Local Law 38 of 2015 (City Legislation)

Local Law 38 phased out the use of No. 6 and No. 4 fuel oils in multiple contexts, including backup power generation.

Local Law 43 of 2010 (City Legislation)

Local Law 43 phased out the use of No. 6 heating fuels in buildings by 2015, and No. 4 fuel oil by 2030.

2019 کا مقامی قانون 97 (City Legislation)

Local Law 97 is one of the most ambitious plans to reduce building emissions in the nation. Most buildings over 25,000 square feet will be required to meet new energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions limits by 2024, with stricter limits coming into effect in 2030. The goal is to reduce the emissions produced by the city’s largest buildings by 40 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050. The law also established the Local Law 97 Advisory Board and Climate Working Groups to advise the City on how best to meet these aggressive sustainability goals.

2021 کا مقامی قانون 154 (City Legislation)

Local Law 154 phases out the use of fossil fuels in new construction starting in 2024, requiring that new buildings be all-electric. New York City is the largest city to require new buildings to be all-electric.

Local Law 32 of 2023 (City Legislation)

Accelerates the phase-out of No. 4 fuel oils by 2027 instead of 2030.

NYC ایکسلریٹر (MOCEJ)

Provides resources, training, and one-on-one expert guidance to help building owners and industry professionals improve energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions from buildings in NYC.

Exposure to Hazardous Materials

Local Law 26 of 1988 (City Legislation)

The Community Right-to-Know (RTK) Program requires that NYC regulate the storage, use, and handling of hazardous substances that pose a threat to public health and the environment. Under the law, businesses are required to file annual reports detailing the quantity, location, and type of every hazardous substance stored in their facilities, which are archived in the Citywide Facility Inventory Database (CFID). The NYC Department of Environmental Protection releases yearly reports analyzing data from the CFID.

E-Designation (OER)

E-Designations identify properties that have environmental requirements relating to air, noise, or hazardous materials that must be investigated or addressed before the property can be redeveloped. An E-designation may be placed on a tax lot by the Department of City Planning or other lead agency in the course of a rezoning or other land use action. Sites with hazardous materials E-designations must be investigated, and OER must approve a cleanup plan based on the investigation’s results before a building permit can be issued.

Voluntary Cleanup Program (OER)

The release of PlaNYC in 2007 established New York City’s brownfield remediation and redevelopment initiatives, and the City created the Mayor’s Office of Environmental Remediation to promote cleanup and redevelopment of vacant contaminated land in NYC. The City signed into law the Brownfield Community and Revitalization Act to address light-to-moderately-contaminated lands that may not be eligible for the New York State Brownfield Cleanup Program and to streamline the cleanup process. In 2010, the City’s Voluntary Cleanup Program began accepting applications. By enrolling in the City Voluntary Cleanup Program, developers can receive grants, fee exemptions, certifications, liability protections, and other incentives to support remediation of contaminated properties. The program also involves release of cleanup plans to the public for notification and comment.

SAFE Disposal Events (DSNY)

SAFE (Solvents, Automotive, Flammables, and Electronics) Disposal events are hosted by DSNY every spring and fall in all five boroughs to provide New Yorkers with an opportunity to safely dispose of chemical products, medical waste, electronics, and other hazardous materials.

Special Waste Drop-off Sites (DSNY)

DSNY also operates a Special-Waste drop-off site in each borough, open a few days each month.

Access to Safe and Healthy Housing

Home Energy Assistance Program (HRA)

the Home Energy Assistance Program (HEAP) is a federally funded program that helps low-income homeowners and renters pay for utility and heating bills. In NYS, HEAP includes a Cooling Assistance benefit to help eligible households buy and install an air conditioner or fan.

NYC ایکسلریٹر (MOCEJ)

Provides resources, training, and one-on-one expert guidance to help building owners and industry professionals improve energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions from buildings in NYC.

Enterprise Green Communities Criteria NYC Overlay (HPD)

All new construction and substantial rehabilitation projects receiving funding from HPD must comply with sustainability and energy efficiency criteria specific to the NYC context. As an alternative, the construction projects may pursue certification with LEED v4, gold or platinum.

گرین ہاؤسنگ پریزرویشن پروگرام (HPD)

GHPP provides low- or no-interest loans to finance energy efficiency and water conservation improvements, lead remediation, and moderate rehabilitation work. The program is designed to assist small- and mid-size building owners improve building conditions and lower operating expenses to ensure the long-term physical and financial health of their buildings and to preserve safe, affordable housing for low- and moderate-income New Yorkers.

ٹھنڈا پڑوس NYC (MOCEJ, formerly ORR)

This 2017 report launched a series of projects to locate cooling interventions in the city’s high-heat neighborhoods in order to mitigate the urban heat island effect. Strategies include targeted street tree planting and strategically installing green infrastructure and cool roofs.

ElectrifyNYC (MOCEJ, formerly MOS)

Launched in 2021 as part of an effort to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions from 1-4 family homes, ElectrifyNYC helps homeowners with green and efficient home upgrades so they can save money, make their homes more comfortable, and breathe cleaner air.

Induction Stove Challenge (NYCHA, NYSERDA, NYPA)

In December, NYCHA, in partnership with NYPA and NYSERDA, issued an RFP for the Induction Stove Challenge – a competitive innovation challenge that calls on appliance manufacturers to design and produce energy-efficient, electric cooking systems to replace existing fossil fuel stoves while avoiding costly electrical upgrades in NYCHA buildings. The Induction Stove Challenge complements an earlier partnership between NYCHA and the non-profit WE ACT for Environmental Justice. RFP responses are due by mid January.

City of Yes Carbon Neutrality (DCP, DOB, FDNY, MOCEJ)

Citywide zoning text change that will clear the way for the many green investments needed in our buildings to support the City’s climate goals.

Exposure to Polluted Water

Green Infrastructure Program (DEP)

DEP has successfully built over 12,000 green infrastructure installations across the city and continues to do so through its Green Infrastructure Program. These installations capture stormwater before it enters the sewer system. The projects range from rain gardens and infiltration basins, to green roofs and playgrounds with underground detention systems.

CSO Long-Term Control Plans (DEP)

On March 8, 2012, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and DEP signed a groundbreaking agreement to reduce CSOs using a hybrid green and gray infrastructure approach. Building on DEP’s ongoing construction of CSO control infrastructure, under this agreement, DEP has developed 11 water-body-specific Long Term Control Plans (LTCP) to reduce CSOs and improve water quality in NYC’s water bodies and waterways. As part of these 11 plans, DEP has committed at over $6B in water quality capital investments. The goal of each LTCP is to identify the appropriate CSO controls necessary to achieve water-body-specific water quality standards, consistent with the Federal CSO Policy and the water quality goals of the Clean Water Act. On June 20, 2023, DEC and DEP signed a modified agreement that includes a commitment by DEP to fund $3.5 billion in green infrastructure projects citywide.

Industrial and Commercial Stormwater Program (DEP)

In the city’s municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4), DEP manages an Industrial and Commercial Stormwater Program to inspect permitted industrial and commercial facilities, enforce regulations, and assess unpermitted facilities to determine whether their stormwater contributions are regulated by the City’s State Pollution Discharge Elimination System (SPDES) permit.

Lead Service Line Replacement Program (DEP)

DEP is working with low-income homeowners to replace privately-owned lead service lines at no cost to the homeowner through the Lead Service Line Replacement Program.

Wetlands Management Framework (NYC Parks)

The 2020 Wetlands Management Framework for New York City provides a 30-year roadmap for the preservation, restoration, and management of all wetlands and streams in New York City with particular focus on those under the care of NYC Parks.

NYC Stormwater Resiliency Plan (MOCEJ, formerly MOR)

This 2021 report outlines the City’s strategies for managing vulnerabilities from extreme rain events, including strategies for improved flash flood response and the introduction of the City’s first Stormwater Flood Maps.

The New Normal Combatting Storm-Related Extreme Weather in NYC (Mayor’s Office)

Immediately after Ida in September 2021, the City released The New Normal, which accelerated much of the City’s stormwater resiliency work and committed to $2.5B in capital projects as well as $25M in programming.

Rainfall Ready (DEP)

Released in summer 2022, illustrating immediate actions the City and New Yorkers can take to prepare for extreme rainfall together.

Long Term Stormwater Resilience Vision (DEP)

Released on the one-year anniversary of Ida in 2022, outlining a green and grey multi-layered strategy to large rainfall events.

Cloudburst Management Program (DEP and Partners)

In January 2023, announced an additional $400M of investment in cloudburst design, expanding this resilient design strategy for large rain events to 4 new neighborhoods (Corona, Kissena Park, East New York, Parkchester) with more to come

Exposure to Climate Change

Get Cool NYC (NYCEM)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, older adults faced an increased risk of indoor heat exposure due to social distancing. Get Cool NYC aimed to address this risk by distributing air conditioning units to low-income older adults, totaling 16,000 AC units in NYCHA homes and more than 56,000 in non-NYCHA homes. This one-time, emergency program helped sensitive populations stay home safely; program participants were three times more likely to report staying home during hot weather in summer 2020 compared to non-participants.

Cool It NYC (NYC Parks)

Cool It! NYC is a Citywide plan to increase the amount of water features, drinking fountains, and tree coverage available to the public during heat emergencies, particularly in neighborhoods that face the dangers of high heat.

ٹھنڈا پڑوس NYC (NYC Parks)

Through the Cool Neighborhoods NYC initiative, NYC Parks has planted 11,634 street and park trees in the most heat-vulnerable (HVI-5) neighborhoods, with an estimated 14,530 more trees to be planted through Spring 2024. The City committed an additional $112 million for the program to plant an estimated 36,000 additional trees per year in HVI-4 neighborhoods through 2026.

Cooling Centers (Multiple Agencies)

New York City opens cooling centers in air-conditioned, public facilities during extreme heat events to help prevent heat-related illnesses or deaths.

Clean Heat for All (NYCHA)